How to use a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for text classification (sentiment analysis) with PyTorch

This tutorial is an introduction to Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for sentiment analysis with PyTorch. There are already a few tutorials and solutions for this task by Gal Hever, Jason Brownlee, or Ben Trevett. However, they are either written in Keras or lack some explanations that I find essential for understanding the underlying mechanics of CNNs as well as their PyTorch specific implementations. I hope this tutorial will therefore help the interested reader to learn more about CNNs and how to implement them for NLP tasks, such as sentiment analysis.

What follows is partially the result of a lecture given by Barbara Plank at LMU in 2024, whom I’d like to thank along with her lab MaiNLP for letting me use some of their code. The theoretical part discussed in this tutorial is also highly indebted to Raschka et al. (2022), whose book on machine learning is for me one of the best resources.

This tutorial is divided into the following chapters:

- Preliminaries imports

- Section 1) Preprocessing the dataset

- Section 2) Theoretical foundations of CNNs for classification

- Section 3) Implementing a CNN with PyTorch

- Section 4) Evaluation of results

Preliminaries: imports

In this tutorial, we’ll be using several different libraries. The following imports shall become clear as we develop our project. I’m using Python 3.12.0.

"""In case the packages are not installed on your machine, let's begin with

installing the ones that we'll need for our task. We can run commands with an

exclamation mark in Jupyter Notebooks."""

!pip install datasets transformers tokenizers scikit-learn torch tqdm

from datasets import load_dataset

import random

from sklearn.metrics import f1_score

from tokenizers import Tokenizer, models, trainers

from tokenizers.pre_tokenizers import Whitespace

import torch.nn as nn

import torch

from tqdm import tqdm

Section 1) Preprocessing the dataset

Loading the data

Our goal is to use data to train a model that can identify the sentiment of a given text instance. In other words, we’ll implement a classifier using supervised learning. The backbone of our sentiment classifier will be a CNN. The data we’re using is taken from Saravia et al. (2018). It consists of English Twitter messages labeled with six “emotions”: anger, fear, joy, love, sadness, and surprise. The dataset is available on HuggingFace and we can load it with the datasets package.

emotions = load_dataset("dair-ai/emotion")

We can have a quick look at how the dataset is splitted and structured.

emotions

DatasetDict({

train: Dataset({

features: ['text', 'label'],

num_rows: 16000

})

validation: Dataset({

features: ['text', 'label'],

num_rows: 2000

})

test: Dataset({

features: ['text', 'label'],

num_rows: 2000

})

})

The labels are already numericalized and the text is lowercased, as we can see when inspecting a single instance.

# The label IDs correspond to the following label order:

labels = ["sadness", "joy", "love", "anger", "fear", "surprise"]

emotions["train"][:5]

{'text': ['i didnt feel humiliated',

'i can go from feeling so hopeless to so damned hopeful just from being around someone who cares and is awake',

'im grabbing a minute to post i feel greedy wrong',

'i am ever feeling nostalgic about the fireplace i will know that it is still on the property',

'i am feeling grouchy'],

'label': [0, 0, 3, 2, 3]}

To allow easier processing, it helps to bind the respective splits to different variables.

train_data = emotions["train"]

validation_data = emotions["validation"]

test_data = emotions["test"]

Tokenization

Before we can use the data to train our model, we need to split up the sentences into tokens. We also want to batch our data so that the model can be trained with more instances at the same time. In this tutorial, we’ll do the tokenization and batching with custom functions.

For our tokenization, we can use a subword tokenization algorithm that is called Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), which was introduced in Sennrich et al. (2016) and is based on an algorithm introduced by Gage (1994). The motivation of this tokenization technique is to let the data decide what subword tokens we’ll have. Another advantage of BPE is that it allows us to deal with unknown words that won’t be part of the training vocabulary but might appear in test data. With BPE, unknown words can be decomposed into their respective subword parts and in this fashion still be processed.

Instead of implementing the BPE tokenizer completely from scratch, we can use the tokenizers package. We also want to pad and truncate each text with a fixed sequence length. If text instances are short, we pad them with 0s; if they are long, we truncate them to the maximum length. This will make the training and inference processes easier.

# We want to begin with only 5000 words in our vocabulary and a fixed sequence

# length of 64

vocab_n = 5000

sequence_len = 64

# Initialize a tokenizer

tokenizer = Tokenizer(models.BPE())

# We can have a preliminary splitting of the text on spaces and punctuations

# with Whitespace()

tokenizer.pre_tokenizer = Whitespace()

# Padding instances to the right with 0s

tokenizer.enable_padding(length=sequence_len)

# Truncating long sequences

tokenizer.enable_truncation(max_length=sequence_len)

# We limit our vocabulary and train the tokenizer

tokenizer_trainer = trainers.BpeTrainer(vocab_size=vocab_n)

tokenizer.train_from_iterator(train_data["text"], trainer=tokenizer_trainer)

After training our custom BPE tokenizer, we aim to transform the raw training data into vector representations, where the input is tokenized and converted into corresponding token IDs. Fortunately, the labels are already numerical. That said, we still need to convert these numerical representations into PyTorch tensors to enable the PyTorch model to process the training instances. To accomplish this, we can write a few custom functions.

def preprocess_text(text: str, tokenizer: Tokenizer):

"""

Helper function to tokenize text and return corresponding token IDs as tensors.

Args:

text, str: Text instance from training data.

tokenizer, Tokenizer: The respective tokenizer to be used for tokenization.

Returns:

Tensor: One-dimensional PyTorch tensor with token IDs.

"""

return torch.tensor(tokenizer.encode(text).ids)

def preprocess_label(label: int):

"""

Helper function to return label as tensor.

Args:

label, int: Label from instance.

Returns:

Tensor: One-dimensional PyTorch tensor containing the label index.

"""

return torch.tensor(label)

def preprocess(data: dict, tokenizer: Tokenizer):

"""

Transforms input dataset to tokenized vector representations.

Args:

data, dict: Dictionary with text instances and labels.

tokenizer, Tokenizer: The respective tokenizer to be used for tokenization.

Returns:

list: List with tensors for the input texts and labels.

"""

instances = []

for text, label in zip(data["text"], data["label"]):

input = preprocess_text(text, tokenizer)

label = preprocess_label(label)

instances.append((input, label))

return instances

Let’s tokenize, pad, and truncate our datasets.

train_instances = preprocess(train_data, tokenizer)

val_instances = preprocess(validation_data, tokenizer)

test_instances = preprocess(test_data, tokenizer)

We shall inspect the second training instance, which was:

i can go from feeling so hopeless to so damned hopeful just from being around someone who cares and is awake.

train_instances[1]

(tensor([ 8, 161, 103, 215, 55, 58, 1173, 36, 58, 807, 587, 1129,

130, 215, 219, 382, 444, 197, 2819, 42, 47, 2670, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0]),

tensor(0))

We can observe that “i” has token index 8. Also notice how “so” appears in the vector representation of the text with index 58 twice. The corresponding label for the sequence is 0 and would be “sadness”.

Batching

Batching the instances will enable the model to process multiple instances simultaneously. To achieve this, let’s write a custom batching function. There are different ways to perform batching, which involves concatenating instances and dividing them into manageable groups. One convenient method is to use the torch.stack() function, which concatenates a sequence of tensors. However, all tensors must be of the same length. Since we already padded and truncated our text instances, this requirement is satisfied.

def batching(instances: list, batch_size: int, shuffle: bool):

"""

Batches input instances along the given size and returns list of batches.

Args:

instances, list: List of instances, containing a tuple of two tensors

for each text as well as corresponding label.

batch_size, int: Size for batches.

shuffle, bool: If true, the instances will be shuffled before batching.

Returns:

list: List containing tuples that correspond to single batches.

"""

if shuffle:

random.shuffle(instances)

batches = []

# We iterate through the instances with batch_size steps

for i in range(0, len(instances), batch_size):

# Stacking the instances with dim=0 (default value)

batch_texts = torch.stack(

[instance[0] for instance in instances[i : i + batch_size]]

)

batch_labels = torch.stack(

[instance[1] for instance in instances[i : i + batch_size]]

)

batches.append((batch_texts, batch_labels))

return batches

Section 2) Theoretical foundations of CNNs for classification

After having prepared our data, we can start with implementing our model. In this tutorial, we’ll be using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), which was introduced in LeCun et al. (1989). The CNN bears resemblance to the Neocognitron (Fukushima 1980) as well as Time-Delay Neural Networks (Waibel et al. 1989). This section is dedicated to the theoretical background of CNNs. In Section 3, we’ll implement the model with PyTorch.

The architecture of a CNN

A CNN is a fully connected network that operates similar to Feedforward Neural Networks (FNNs) in a feedforward fashion. The input is processed along layers and forwarded to the final layer, which can be used for predictions. The idea of a CNN is to consecutively extract salient features, such as shapes in terms of their respective pixels, building an abstract feature hierarchy for any given input. In this fashion, the model will be aligned through its training to reoccurring patterns, which it can “recognize.” It’s no surprise that CNNs were invented for handwritten digit recognition in images.

The basic architecture of a CNN is as follows: For any given input, the CNN uses convolutions, that is, a filter (also called kernel) technique to extract local features from the input (e.g., pixels). After this filter has shifted over the whole input, the extractions are combined together into feature maps and then transformed with pooling. Pooling helps with singling out dominant features and allows to reduce the dimensions of the feature maps. This process can be repeated multiple times where additional filters can shift again over the pooled output from previous convolutions. Finally, for the last part of the network a FNN is used to produce logits for the desired task.

One CNN layer consists of one convolutional and one pooling layer.

Filtering

Filters shift over the input. If the input is one-dimensional, that is, a vector, then the filter is itself a one-dimensional, usually smaller vector. If the input is two-dimensional, a matrix, then the filter needs to be a matrix, too.

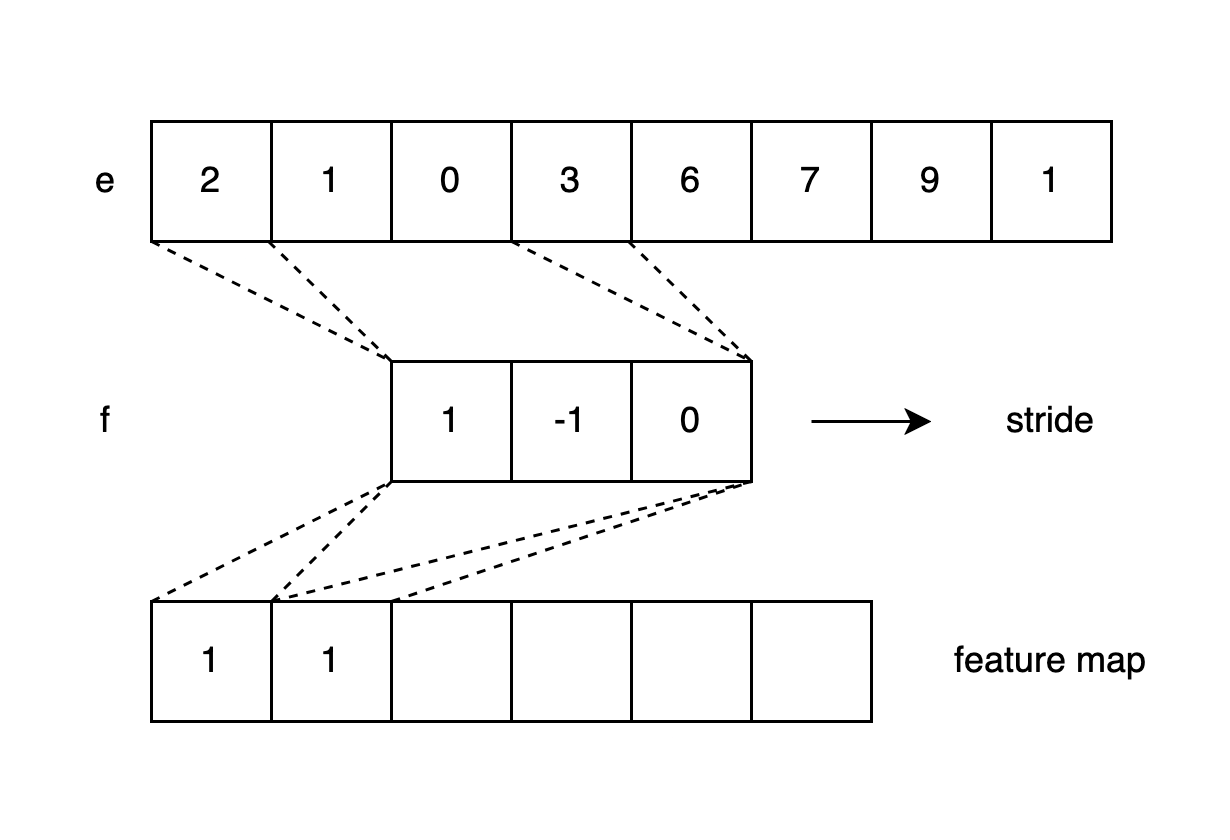

For a one-dimensional input of length \(n=8\), such as \([2, 1, 0, 3, 6, 7, 9, 1]\), we can define a filter of size \(m=3\), such as \([1, -1, 0]\). As the shifting starts, we’ll multiply the first three entries of the input vector with the filter:\([2, 1, 0] * [1, -1, 0]^T = 1\) In this fashion, we obtain the first entry for our feature map: \(y[0]=1\). Next, we shift the filter one step forward (with stride=1) and repeat the multiplication, until the filter reaches the end of the input, bounded by its last index (see Fig. 1). We can formalize this operation between the filter vector f and the input vector e as follows:

\[e*f\rightarrow y[i] = \sum_{k=1}^m{e[i+k-1]\cdot f[k]}\]In fact, the filter size is a hyperparameter that can be set to any positive integer smaller than the input length. In those scenarios where the filter is very large and exceeds the input, we can pad the input with additional elements so that the filter operation would be possible. There a several padding strategies to avoid that elements from the middle of the input will be covered more frequently by the filter than those from the edges.

In our implementation (Section 3), we’ll be using the same padding strategy, which adds zeros to the input on all sides so that the output of the filter operation can have the same size as the input. Therefore, the amount of padding will depend on the size of the filter(/kernel). Consider Raschka et al. (2022, p. 457) for further details.

Fig. 1: One-dimensional convolution

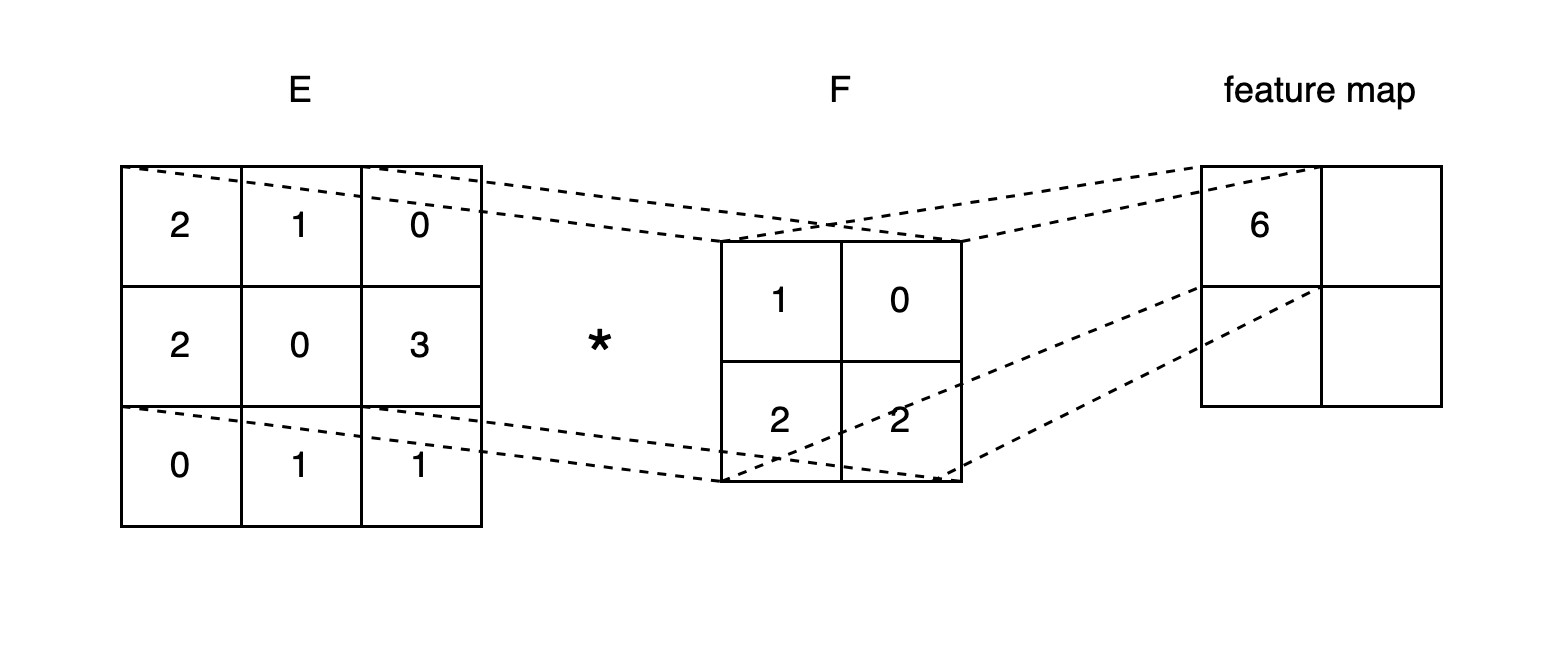

The convolution described previously for one-dimensional inputs works in exactly the same way for two-dimensional inputs (see Fig. 2). If \(E_{n_1\times n_2}\) is the input matrix and \(F_{m_1\times m_2}\) the filter where \(m_1\leq n_1\) and \(m_2\leq n_2\), for each stride we can compute our feature map as follows:

\[E*F\rightarrow y[i][j] = \sum_{k_1=1}^{m_1}\sum_{k_2=1}^{m_2}{e[i+k_{1}-1][j+k_{2}-1]\cdot f[k_1][k_2]}\]with \(y[i][j]\) corresponding to the respective feature representation in the map, which is also a matrix.

Fig. 2: Two-dimensional convolution

Subsampling layers: pooling

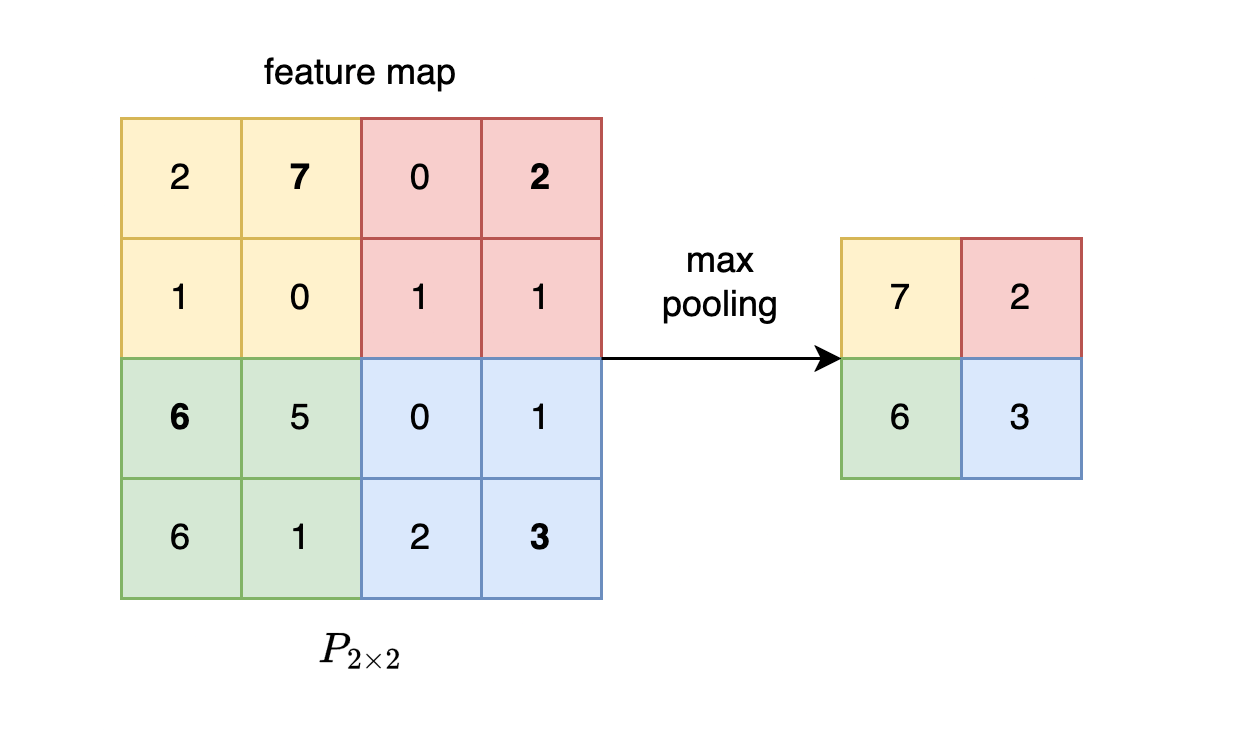

The idea of pooling layers is to reduce the size of the feature map and abstract from the features, either by picking out one local maximum feature value or averaging over a group of feature values. The former strategy is called max pooling, the latter is called average pooling. We’ll focus on max pooling (see Fig. 3).

A pooling layer can be defined as \(P_{n_1 \times n_2}\), where the subscript indicates the area size over which the max operation is performed, while shifting across the entire map.

Fig. 3: Max pooling

Adding activation functions

A FNN usually consists of a layer that is defined as \(z=Wx + b\) where \(W\) are the weights and \(b\) is an extra bias for input \(x\). Such a layer is often wrapped by a non-linear activation function \(\sigma\), as in \(A=\sigma (z)\). We adapt the convolutional layer so that it resembles the previous FNN construction. Let \(c = E*F + b\) be our layer with an additional bias term \(b\). As with the FFN we can wrap an activation function \(\sigma\) around \(c\). In many CNN implementations, the ReLu activation function is used for this purpose.

LeCun et al. (1989) published their paper titled ‘Handwritten Digit Recognition with a Back-Propagation Network.’ Let us now examine which parts of a CNN are trainable using back-propagation. It’s the convolutional layers (filters) with their weights \(F\) and biases \(b\) (if included) that can be updated through back-propagation, guided by a loss function and gradient optimization. Recall that most CNNs also include a final fully connected feedforward neural network (FNN) layer for producing the output, and this layer is trainable as well. However, the pooling layer is not involved in the training process, as it does not contain learnable parameters.

Multiple channels

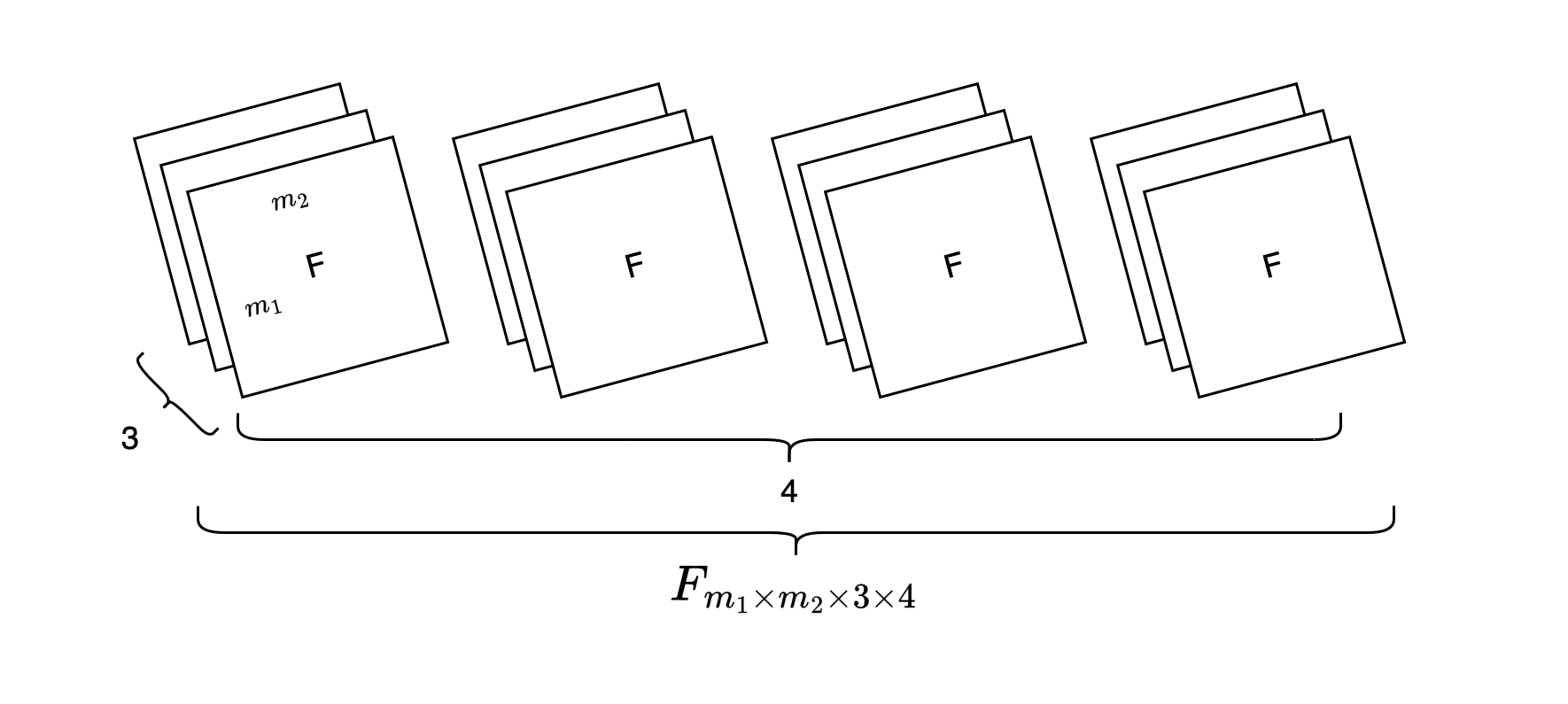

The input to a CNN can be greater than one. If we’re dealing with images that are encoded in terms of RGB colors, we can split up the input into three two-dimensional matrices corresponding to red, green, and blue color information and feed them to the CNN. Each input matrix would be called one channel. For this matter, in most CNN implementations the convolutional layers expect an input with 3 dimensions where \(E_{n_1\times n_2 \times c_{in}}\) would be the input of dimensions \(n_1\times n_2\) times \(c_{in}\), such as \(c_{in} = 3\) for three different color matrices.

The further processing of the input allows a lot of variability: Each \(c_{in}\) input will have its own filter. The filters can be also stored as three-dimensional tensors: \(F_{m_1\times m_2 \times c_{in}}\). Usually, the filtered results from each respective input will be element-wise added to create the output feature map. But sometimes it also helps to have multiple feature maps as outputs to capture different aspects from the input. In this case, the filters can be changed to four-dimensional tensors: \(F_{m_1\times m_2 \times c_{in}\times c_{out}}\) where \(c_{out}\) determines the numbers of feature maps that we want (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Multiple filters (kernels) for three input channels, producing four feature maps

Note, if we have for example four feature maps, we’ll also need four pooling layers. As the size of convolutional layers changes we’ll also have more parameters to train. This being said, remember that a FNN processing an input image would require weights of same size for its first layer. In contrast, the parameters of CNNs are bounded by the filter size. LeCun et al. (1989, p. 399) describe this aspect as “weight sharing” and note as one distinctive feature of CNNs that they significantly reduce the amount of parameters to be trained.

Section 3) Implementing a CNN with PyTorch

Let’s begin with defining our classifier model. It’s reasonable to use embeddings for our input tokens. For that matter, our model should start with an embedding layer. The embeddings will be handed over to our CNN, which will consist of two convolutional layers with two different filters(/kernels). Finally, the input abstracted throughout the network needs to be passed to a final FFN layer for our sentiment prediction.

To build an intuition for the whole process, let’s think again of the input. The input is a sequence (a tweet) from our data. This sequence will be translated into its correspoding token representation based on our custom trained BPE encoder. In other words, any incoming sequence will be a tensor of different indices. Next, the indices are handed over to our embedding layer, which serves as a look-up table for all tokens in the vocabulary and assigns the embedding representation to the input indices. This layer is a simple linear layer that is going to be trained along with the whole network later on. The initial values of the embeddings are random numbers.

Up to this point, we can think of two strategies to run a first convolution over the input. If the input is 12 tokens long and each token has an embedding vector of size 300, the input to a potential convolutional layer would be \(12 \times 300\). The first strategy could be to apply a two-dimensional filter striding over this input matrix. The second strategy would be to use a one-dimensional filter that is going over one embedding dimension per time for the whole sequence, that is, over \(12 \times 1\) but with 300 channels for all embedding dimensions. If we want the output to be of the same length as the input, that is, 12, we need to pad the input to adjust for the filter length.

In our implementation, we shall try the second strategy. Remember that the input channels will all be added together so before having our 300 embedding dimensions shrunk to one, we shall define an appropriate output channel size for the convolution. In other words, we’ll use as many as 100 filters for example to create an output of 100 dimensions for each respective input token.

After having defined our model, we need to implement the training loop with a fitting method. To understand our training process we also need an evaluation mechanism. Finally, we need another method for making predictions from the trained classifier.

class CNN_Classifier(nn.Module):

"""

CNN for sentiment classification with 6 classes, consisting of an embedding

layer, two convolutional layers with different filter sizes, different

pooling sizes, as well as one linear output layer.

"""

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# We can implement embeddings as a simple lookup-table for given word

# indices

self.embedding = nn.Embedding(tokenizer.get_vocab_size(), 300)

# One-dimensional convolution-layer with 300 input channels, and 100

# output channels as well as kernel size of 3; note that the

# one-dimensional convolutional layer has 3 dimensions

self.conv_1 = nn.Conv1d(300, 100, 3, padding="same")

# Pooling with with a one-dimensional sliding window of length 3,

# reducing in this fashion the sequence length

self.pool_1 = nn.MaxPool1d(3)

# The input will be the reduced number of maximum picks from the

# previous operation; the dimension of those picks is the same as the

# output channel size from self.conv_1. We apply a different filter of

# size 5.

self.conv_2 = nn.Conv1d(100, 50, 5, padding="same")

# Pooling with window size of 5

self.pool_2 = nn.MaxPool1d(5)

# Final fully connected linear layer from the 50 output channels to the

# 6 sentiment categories

self.linear_layer = nn.Linear(50, 6)

def forward(self, x):

"""

Defining the forward pass of an input batch x.

Args:

x, tensor: The input is a batch of tweets from the data.

Returns:

y, float: The output are the logits from the final layer.

"""

# x will correspond here to a batch; therefore, the input dimensions of

# the embedding will be by PyTorch convention as follows:

# [batch_size, seq_len, emb_dim]

x = self.embedding(x)

# Unfortunately the embedding tensor does not correspond to the shape

# that is needed for nn.Conv1d(); for this reason, we must switch its

# order to [batch_size, emb_dim, seq_len] for PyTorch

x = x.permute(0, 2, 1)

# We can wrap the ReLu activation function around our convolution layer

# The output tensor will have the following shape:

# [batch_size, 100, seq_len]

x = nn.functional.relu(self.conv_1(x))

# Applying max pooling of size 3 means that the output length of the

# sequence is shrunk to seq_len//3

x = self.pool_1(x)

# Output of the following layer: [batch_size, 50, seq_len//3]

x = nn.functional.relu(self.conv_2(x))

# Shrinking the sequence length by 5

x = self.pool_2(x)

# print(x.shape)

# At this point we have a tensor with 3 dimensions; however, the final layer

# requires an input of size [batch_size x 50]. To get this value we can

# aggregate the values and continue only with their mean

x = x.mean(dim=-1)

# In this fasion, the linear layer can be used to make predictions

y = self.linear_layer(x)

return y

def fit(self, train_instances, val_instances, epochs, batch_size):

"""

Gradient based fitting method with Adam optimization and automatic

evaluation (F1 score) for each epoch.

Args:

train_instances, list: List of instance tuples.

val_instances, list: List of instance tuples.

epochs, int: Number of training epochs.

batch_size, int: Number of batch size.

"""

self.train()

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(self.parameters())

for epoch in range(epochs):

train_batches = batching(

train_instances,

batch_size=batch_size,

shuffle=True)

for inputs, labels in tqdm(train_batches):

optimizer.zero_grad()

outputs = self(inputs)

loss = nn.functional.cross_entropy(outputs, labels)

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

train_f1 = self.evaluate(train_instances, batch_size=batch_size)

val_f1 = self.evaluate(val_instances, batch_size=batch_size)

print(f"Epoch {epoch + 1} train F1 score: {train_f1}, validation F1 score: {val_f1}")

def predict(self, input):

"""

To make inferences from the model.

Args:

input, tensor: Single instance.

Returns:

int: Integer for most probable class.

"""

self.eval()

outputs = self(input)

return torch.argmax(outputs, dim=-1)

def evaluate(self, instances, batch_size):

"""

To make evaluations against the gold standard (true labels) from the

data.

Args:

instances, list: List of instance tuples.

batch_size, int: Batch size.

Returns:

float: Macro F1 score for given instances.

"""

batches = batching(instances, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=False)

true = []

pred = []

for inputs, labels in batches:

true.extend(labels)

pred.extend(self.predict(inputs))

return f1_score(true, pred, average="macro")

We can now train our model.

classifier = CNN_Classifier()

classifier.fit(train_instances, val_instances, epochs=5, batch_size=16)

100%|██████████| 1000/1000 [00:26<00:00, 37.29it/s]

Epoch 1 train F1 score: 0.6349625340555586, validation F1 score: 0.5885997748733948

100%|██████████| 1000/1000 [00:27<00:00, 36.16it/s]

Epoch 2 train F1 score: 0.9181883927660527, validation F1 score: 0.8391332797173209

100%|██████████| 1000/1000 [00:31<00:00, 31.86it/s]

Epoch 3 train F1 score: 0.9548322090243025, validation F1 score: 0.8665508014136801

100%|██████████| 1000/1000 [00:30<00:00, 32.63it/s]

Epoch 4 train F1 score: 0.9715161826479329, validation F1 score: 0.851259672136001

100%|██████████| 1000/1000 [00:33<00:00, 30.13it/s]

Epoch 5 train F1 score: 0.9830196392925995, validation F1 score: 0.8649424900902641

Section 4) Evaluation of results

After we have trained our model, we can use our test set to see how well it predicts sentiments for unseen examples.

f1_test = classifier.evaluate(test_instances, batch_size=16)

print(f"F1 score for test set: {f1_test}")

F1 score for test set: 0.8403978699590415

Hyperparameters

There are many hyperparameters in the entire modeling process that we can adjust to achieve even better results. These include different layer sizes, filters, poolings, and more efficient optimization techniques. Typically, dropout is applied during the training of such models to prevent overfitting. It is also worthwhile to explore the possibility of using pre-trained embedding representations.

The Jupyter notebook for this project can be found here: https://github.com/omseeth/cnn_sentiment_analysis

References

Fukushima, K. (1980). Neocognitron: A self-organizing neural network model for a mechanism of pattern recognition unaffected by shift in position. Biol. Cybernetics 36, pages 193–202.

Gage, P. (1994). A new algorithm for data compression. C Users J., 12(2):23–38.

LeCun, Y., Boser, B., Denker, J., Henderson, D., Howard, R., Hubbard, W., and Jackel, L. (1989). Handwritten digit recognition with a back-propagation network. In Touretzky, D., editor, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 2. Morgan-Kaufmann

Saravia, E., Liu, H.-C. T., Huang, Y.-H., Wu, J., and Chen, Y.-S. (2018). CARER: Contextualized affect representations for emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 3687–3697, Brussels, Belgium. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Sebastian, R., Yuxi, L., and Mirjalili, V. (2022). Machine Learning with PyTorch and Scikit-Learn: Develop machine learning and deep learning models with Python. Packt Publishing.

Sennrich, R., Haddow, B., and Birch, A. (2016). Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. In Erk, K. and Smith, N. A., editors, Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 1715–1725, Berlin, Germany. Association for Computational Linguistics

Waibel, A., Hanazawa, T., Hinton, G., Shikano, K. and Lang, K. J. (1989). Phoneme recognition using time-delay neural networks. In IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, vol. 37, no. 3, pages 328-339.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: