Using LLMs in Syntactic Research

Abstract Large language models (LLMs) have revolutionized natural language processing. This study investigates their potential for replicating and contributing to syntactic research. I leverage GPT-3.5 Turbo to reproduce Experiment 2 from Salzmann et al. (2022), which explored Principle C (coreference restrictions) in German. The LLM successfully replicated human behavior in confirming Principle C’s influence. However, unlike human participants, GPT-3.5 Turbo did not exhibit sensitivity to syntactic movement, but to argument and adjunct positions, suggesting a potential difference in underlying processing mechanisms. These findings highlight the potential of LLMs for probing syntactic principles as well as linguistic phenomena more generally but also raise questions about their ability to mirror human language processing. I discuss the methodological implications of using LLMs for linguistic inquiry and the potential for uncovering insights into their inner workings.

1 Introduction

The advent of large language models (LLMs) through the Transformer architecture (Vaswani et al., 2017) has led to models with unprecedented capabilities. This contribution attempts to harness these capabilities to reproduce an empirical experiment from Salzmann et al. (2022) with one Transformer based model, GPT 3.5 Turbo developed by OpenAI.

The background to the experiment is an investigation of Principle C (also called Condition C). According to syntactic theory, Principle C governs the possibilities of coreference between pronouns and R-expressions (i.e., proper names and definite determiner phrases). However, how the principle works remains a matter of debate (Adger et al., 2017; Bruening and Khalaf, 2018; Salzmann et al., 2022; Stockwell et al., 2021). For that matter, Salzmann et al. (2022) developed several experiments to explore the principle in German contexts. This paper focuses on their second experiment, Experiment 2, where the authors attempted with a 2 x 2 x 2 experimental design to investigate whether participants reconstructed the syntactic hierarchy of given sample sentences when asked if different interpretations were possible (Salzmann et al., 2022, 601).

To reproduce Experiment 2, GPT 3.5 Turbo was queried with the exact same items that were used in the original work by Salzmann et al. (2022). I employed diverse prompt types, including zero-shot and one-shot, and varied sizes of iterations. In order to match the identical quantity of data points collected from 32 participants in Salzmann et al. (2022), I finally chose the outcomes of a configuration of four iterations with a zero-shot prompt to query GPT 3.5 Turbo for fitting a generalized linear mixed model. With this model, I tested the same three hypotheses from Experiment 2 in Salzmann et al. (2022).

I report the following results: In line with human participants, the LLM qualified sentences with referring expressions in such a fashion that the influence of Principle C for respective cases with R-expressions and pronouns is attested. In contrast to the human proportion of answers, GPT 3.5 Turbo’s output did not indicate a significant influence of movement when interpreting the test item sentences. If movement is understood as a variable for reconstruction, it appears that the LLM does not reconstruct the pre-moved positions of the phrases. Finally, a significant influence of position of R-expressions in either arguments or adjuncts can be shown with GPT 3.5 Turbo. Overall, GPT 3.5 Turbo’s judgments of sentences differ from those of humans in more ambiguous cases. However, whether movement and reconstruction play a role in human interpretations is neither fully clear from Experiment 2, as Salzmann et al. (2022) conclude in their discussion of the original experiment.

The novel possibility to reproduce an empirical experiment in linguistics with LLMs also raises many methodological questions. Are LLMs like GPT 3.5 Turbo computational accounts of how humans process language (Blank, 2023)? Can they be deployed to test hypotheses in syntax as well as other linguistic fields? Even if these questions remain open to debate, querying LLMs with test items from linguistics would also provide us with valuable insight into the ”metacognition” of these models (Begus et al., 2023). Knowing how the models respond can help engineers with improving their performance.

In Section 2, I will introduce Principle C and the syntactic considerations that led to Experiment 2 in Salzmann et al. (2022). The reports of the original experiment will be reported in Section 3. I will discuss in Section 4 the prompts and details used to query GPT 3.5 Turbo with the items from Salzmann et al. (2022). I will summarize the LLM’s results in Section 4.2. Finally, I will provide a short discussion of possible implications of using LLMs in linguistic research in Section 5.

2 Syntactic principle for referring expressions

Several foundational assumptions hold in generative syntax. Generally, its goal is to analyze language by assuming that rules generate well-formed patterns. Some of these rules, also called principles, are considered to be universal, others only apply to specific languages. It is further assumed that each language is structured hierarchically where the constituents of a syntactically formed phrase can be moved within its hierarchy to accommodate the large variety of linguistic possibilities. When a constituent is being moved, analysis states that it is generally assumed that it leaves a trace behind. However, many movements are also restricted, for example by the depth of embedding of each constituent within the hierarchy.

Among the syntactic principles, generative syntax has identified three types that restrict in particular co-reference of noun phrases (R-expressions, pronouns, anaphors). These types are called Principle A, B, and C. Principle C will be of interest to us in this contribution.

Principle C states that a pronoun cannot refer to an R-expression that it c-commands. R-expressions are proper names or definite determiner phrases, such as ”Mary” or ”the dog”. C-command is a syntactic constraint where a constituent within a phrase’s hierarchy would occupy a structurally higher position than another one from which syntactic restrictions as in Principle C follow. For example:

(1) \(^*\)He\(_{i}\) thinks that Peter\(_{i}\) is the happiest.

is ungrammatical according to Principle C when it is assumed that the pronoun should refer to the noun (see indices). It occupies a structurally higher position than the R-expression Peter. For the same reasons, a sentence like

(2) \(^*\)[Which of Lara\(_{i}\)’s sweaters]\(_{1}\) do you think she\(_{i}\) likes __\(_{1}\)?

is considered ungrammatical, even if the R-expression Lara appears on the surface before the pronoun. This can be explained with reconstructing to the trace of the movement of the wh-phrase (consider index 1 and square brackets) which occupies a lower position than the pronoun before its movement. This is also called an A’-movement since the movement does not affect the type of phrase.

In their paper, ”Condition C in German A’-movement: Tackling challenges in experimental research on reconstruction”, Salzmann et al. (2022) analyze Principle C (also called Condition C) within particular contexts. Their research follows a shift in syntax where principles that were suggested by syntactitians based on introspective judgements (sometimes described as armchair syntax) are checked through experimental setups. If principles can be confirmed in a variety of linguistic examples by a sufficient size of native speakers, the empirical evidence provides an additional justification for them. If a pattern is equivocally observed, it might not apply in a principled sense.

The aim of Salzmann et al. (2022) is to examine the workings of Principle C within three contexts. I will explain them briefly. Context 1) When the R-expression is part of an adjunct, as opposed to when it is part of an argument, the established view states that there is no Principle C reconstruction (Lebeaux, 1991; Salzmann et al., 2022). Context 2) Principle C is always violated whenever the R-expression is contained within a predicate. The containment of an R-expression within an argument does not always lead to a violation, contrary to the assumption in Context 1 (Huang, 1993; Salzmann et al., 2022). Context 3) Condition C is less strict with relative clauses than with wh-movement (Citko, 1993; Salzmann et al., 2022).

Salzmann et al. (2022) conducted three experiments in German to examine the previously mentioned syntactic phenomena. This paper focuses on their second experiment (Salzmann et al., 2022, pp. 601-609, the experiment was also registered at https://osf.io/mjgpz).

In Experiment 2, Salzmann et al. (2022) investigate coreference between pronoun and R-expression in embedded clauses. The clauses have either moved or in situ wh-phrases, serving either as objects or as subjects. Additionally, it is investigated whether the position of an R-expression as part of an argument or and adjunct makes a difference. The following two examples from Salzmann et al. (2022, 603) illustrate the conditions in Experiment 2:

(3)… [welche Geschichte im Buch über Hanna] sie __ ärgerlich fand.

’which story in the book about Hanna she found upsetting.’

(4)… [welche Geschichte über Hanna] __ sie verärgert hat.

’which story about Hanna upset her.’

Note in (3) that the object is moved and the R-expression Hanna serves as an adjunct to ”im Buch”. If Principle C were to have its assumed force in all instances, one would assume for (3) that the pronoun cannot refer to the R-expression. (Though the established view has noticed that the adjunct position indicates a less strict application of Principle C.) In (4), the wh-phrase serves as the subject which is moved and the R-expression is part of an argument. One would assume in contrast to the previous example that the pronoun can refer to the R-Expression. Also consider the for the depth of embedding and hence the structural hierarchy in both examples for the assumptions.

The aim of Experiment 2 in (Salzmann et al., 2022) is to create a statistical baseline for syntactically well-formed clauses (no violation of Principle C) through positive responses as well as a percentage of responses for those examples where Principle C would be violated if movement is assumed. If no violation in terms of negative responses is reported for ungrammatical examples, Salzmann et al. (2022) consider surface factors as another influence for the acceptability of coreference between R-expression and pronoun in such cases.

Salzmann et al. (2022, 603-604) test three hypotheses in their experiment to consider the effect of Principle C (also called Condition C) in the previously mentioned variety of contexts:

- H1 Condition C hypothesis: R-expressions cannot be coreferential with a c-commanding expression.

- H2(a) Reconstruction hypothesis: the base position of moved phrases matters for Condition C.

- H2(b) Surface hypothesis: the surface position of moved phrases matters for Condition C.

- H3 Argument/adjunct asymmetry hypothesis: in contrast to argument po- sitions, there is no reconstruction if the R-expression is part of an adjunct.

H1 assumes that phrases with an in situ subject receive more positive responses for the subject than for the object, as coreference with the object would clearly violate Principle C. Consider the following example:

(5) \(^*\)Jim erklärt, dass er die neue Geschichte über Mert ärgerlich fand.

’Jim explains that he found the new story about Mert upsetting.’

That the pronoun ”er” refers to Mert contradicts our syntactic intuition.

If H1 is confirmed, the authors investigate with H2 if more positive responses for a moved subject can be observed than with a moved object, that is, whether Principle C also holds with movement (H2(a)). If there is a significant difference between H2(a) and H1, then it is assumed that H2(b) would be confirmed, that is, surface positions influence the force of Principle C in case that the surface effects differ for objects and subjects. Finally, H3 investigates the difference of responses with instances where the R-expression is positioned as an adjunct compared to those within argument structures.

3 Experimental results from 32 participants

In this section, I will briefly describe the experimental setting of Experiment 2 from (Salzmann et al., 2022) and report their results.

3.1 Experimental setting

To test their hypotheses, Salzmann et al. (2022) developed a 2 x 2 x 2 design where the first factor was Phrase (containment of R-expression either within the subject or the object), the second Position (R-expression either as argument or adjunct) and the third Movement (in situ or moved). 32 participants were recruited via www.prolific.co. They were given 78 stimuli which comprised 32 critical items, 44 fillers, and 2 additional items for exploration.

The general set-up of each experimental round consisted in a shown example sentence with two R-expressions and a pronoun. The sentence was followed by two binary questions. Before the start of the experiment, the participants received an instruction with an example that deliberately allowed two interpretations for resolving the references of the example sentence. The participants were told to answer ”Yes” and ”Yes” in such cases. Generally, a sentence such as (5) was accompanied with two questions of the following type: Q1) ”Can this sentence be interpreted that Jim found a story upsetting?” (asking about the subject from the matrix clause ’Jim explains that…’) and Q2) ”Can this sentence be interpreted that Mert found a story upsetting?” (asking about the subject and/or object, depending on the respective condition, from the embedded clause). To avoid the order of Q1 and Q2 as a confound, the questions were randomly switched. Salzmann et al. (2022) collected the respective ”Yes” and ”No” answers for all stimuli. On average, the authors report that the experiments took 24 minutes until completion.

3.2 Results from 32 participants

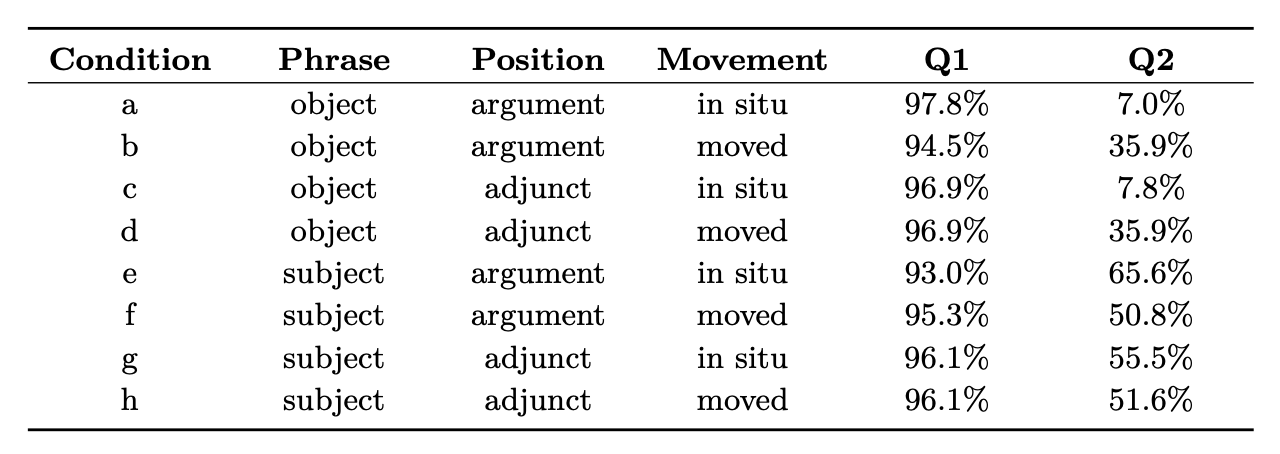

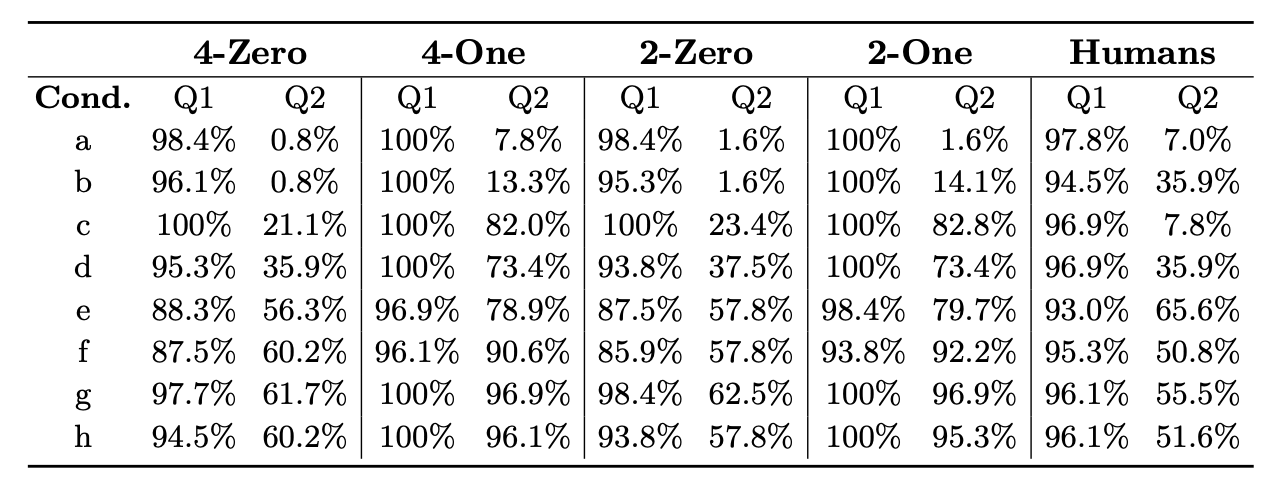

For their 32 participants, Salzmann et al. (2022) report the results for all conditions as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Results of Experiment 2 with proportion of positive answers

Noticeably, the interpretations of questions of type Q1 with respect to the refer- ring R-expression were accepted in nearly all stimuli. This comes as no surprise as its intention was to establish a baseline for syntactically well-formed patterns where the subject from the matrix clause occupies the structurally highest position. Given that some noise is considerably part of every empirical evaluation, 100% positive answers for the well-formed examples would be more concerning. A greater difference is observable for those readings that were elicited with Q2. Q2 received a proportion of more than 50% positive answers where the R-expression was part of a subject phrase. To a lesser degree, Q2 was accepted when it was contained within an object phrase, almost never when the R-expression stayed in situ (consider example (5)).

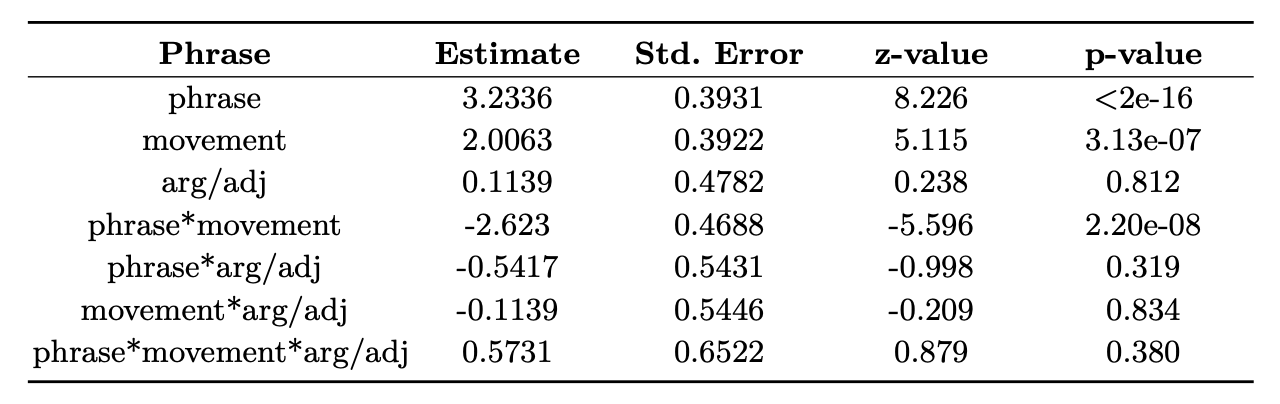

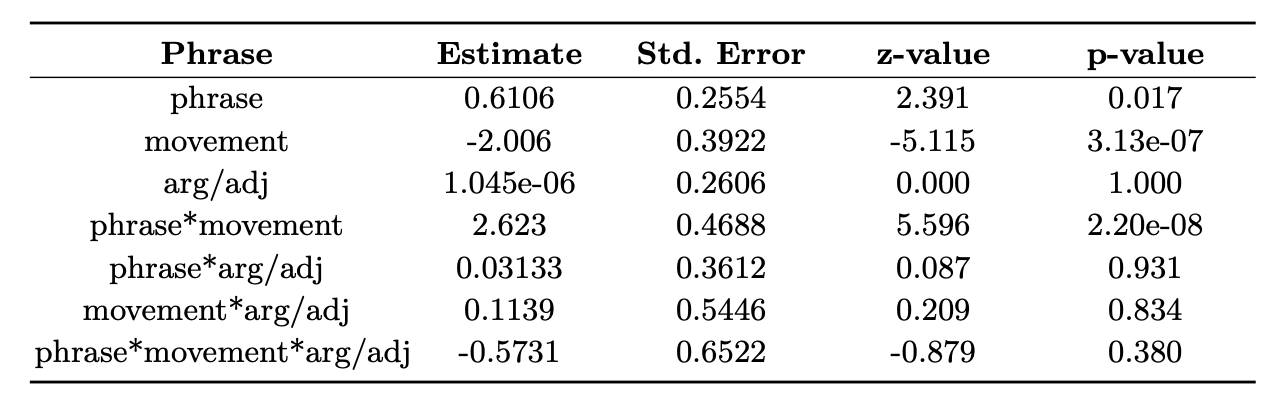

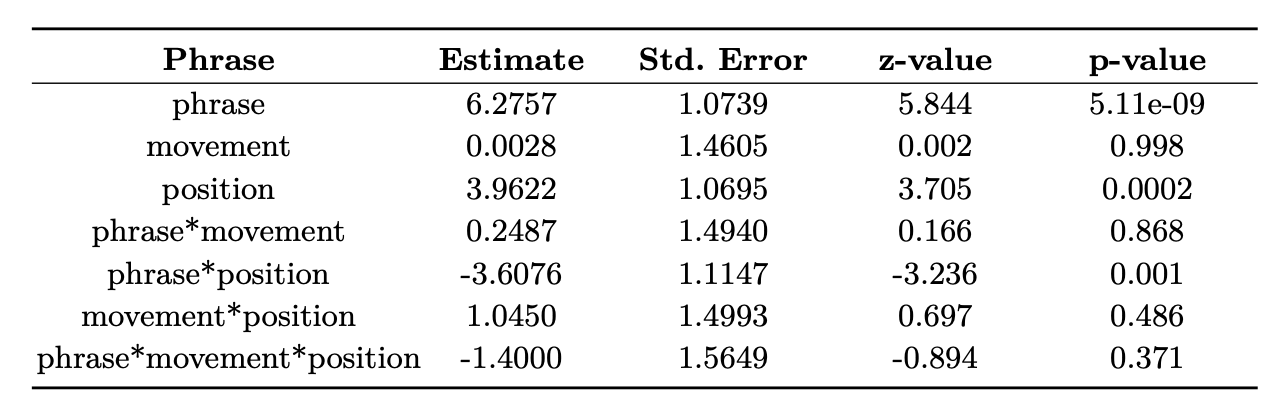

With their findings, the authors fit two generalized linear mixed models, following the recommendations of Bates et al. (2015), where the items are considered as random effects. For both models the baseline of Phrase was ’object’ and for Position ’argument’. To test all hypotheses two contrast encodings were necessary so that Movement received ’in situ’ as its baseline in Model 1 and ’moved’ in Model 2. I report their results in Table 2 and 3 where Position was originally called ”arg/adj”.

Table 2: Generalized linear mixed model results from Experiment 2 (Model 1)

Table 3: Generalized linear mixed model results from Experiment 2 (Model 2)

Salzmann et al. (2022, 606) use Model 1 and 2 to validate or reject their hypotheses. They report an effect of Phrase for the levels ’in situ’ and ’argument’ with respect to the other factors: z = 8.226, p < 0.001 in Model 1, so H1 is being confirmed. The reasoning behind this is that for sentences with subject, in situ, argument, such as in Condition e:

(6) Jim erklärt, dass die neue Geschichte über Mert ihn verärgert.

’Jim explains that the new story about Mert upsets him.’

there is no c-command for the pronoun over the R-expression in the embedded clause, compared with sentences with object, in situ, argument Condition a, as in:

(7) Jim erklärt, dass er* die neue Geschichte über Mert ärgerlich fand.

’Jim explains that he found the new story about Mert upsetting.’

An effect of Phrase was also noticed within the levels of ’moved’ and ’argument’ with respect to the other factors: z = 2.391, p = 0.017 in Model 2. This confirms H2(a) of their hypotheses: that the base position of moved phrases matters for Principle C. Compare Condition c (not the principle):

(8) Lisa erzählt, [welche Geschichte über Hanna] sie __ ärgerlich fand.

’Lisa tells which story about Hanna she found upsetting.’

with Condition g:

(9) Lisa erzählt, [welche Geschichte über Hanna] __ sie verärgert hat.

’Lisa tells which story about Hanna upset her.’

Salzmann et al. (2022) also explain in their study pre-registration: ”If there is reconstruction for Principle C, we should see the same effect in the conditions with wh-movement as in the conditions without wh-movement, irrespective of the differences in surface structure.”

The authors further confirm hypothesis H2(b) (the relevance of surface positions) because an interaction between Movement and Phrase is found in the level ’argument’ of the other factor: |z| = 5.596, p < 0.001 in both models. The reasoning is that Principle C would be reduced in contexts with movement compared to those without because on the surface the moved phrase would not look like a violation of the principle.

Finally, hypothesis H3 (argument/adjunct asymmetry) is not confirmed as there is overall no effect of Position and neither an interaction between Phrase and Position (arg/adj) within the level of ’moved’ (z = 0.087,p = 0.931 in Model 2) nor between Movement and Position (arg/adj) within ’object’ (|z| = 0.209, p = 0.834 in Model 1 and 2). Salzmann et al. (2022) argue that H3 can also only hold if H2(a) is borne out.

4 Experimental results from LLM

In section 4, I will discuss the model and prompts used in the experiment and report its results.

4.1 Experimental setting

The experiment was executed with the updated GPT 3.5 Turbo (gpt-3.5-turbo- 0125) large language model from www.openai.com. The model’s training data dates up to September 2021. For the experiment, GPT 3.5 Turbo is queried twice with an adjusted prompt for each test sentence with Q1 in the first round and Q2 in the second. This process was repeated for two and four iterations, leading to an overall data with 512 and 1024 data points for each type of questions (Q1 or Q2). Four iterations led to the same amount of data points as in Experiment 2 from Salzmann et al. (2022). The temperature of the model, which renders its answers more deterministic, was set to 0. The role – an option by OpenAI to further customize the prompts – used for the queries was the default ”user”.

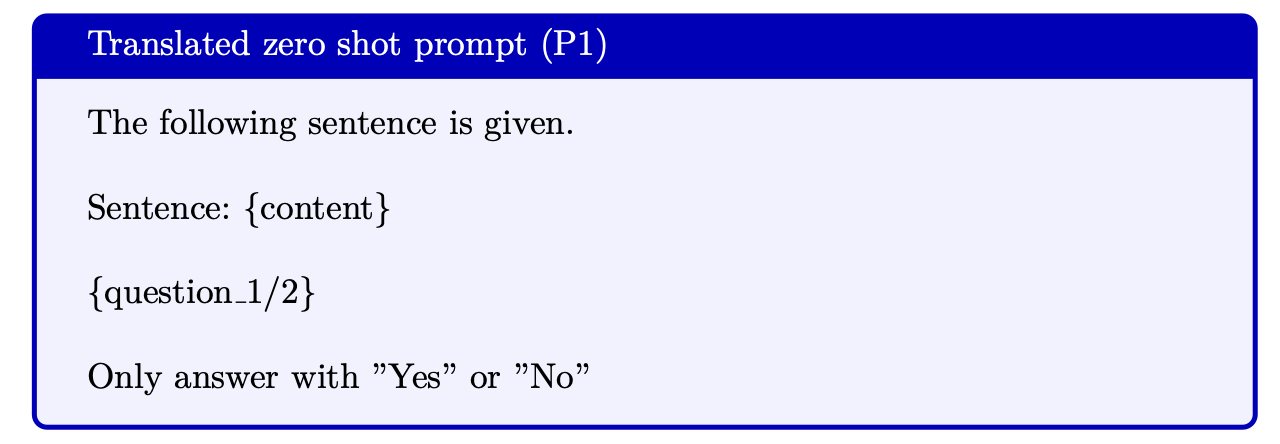

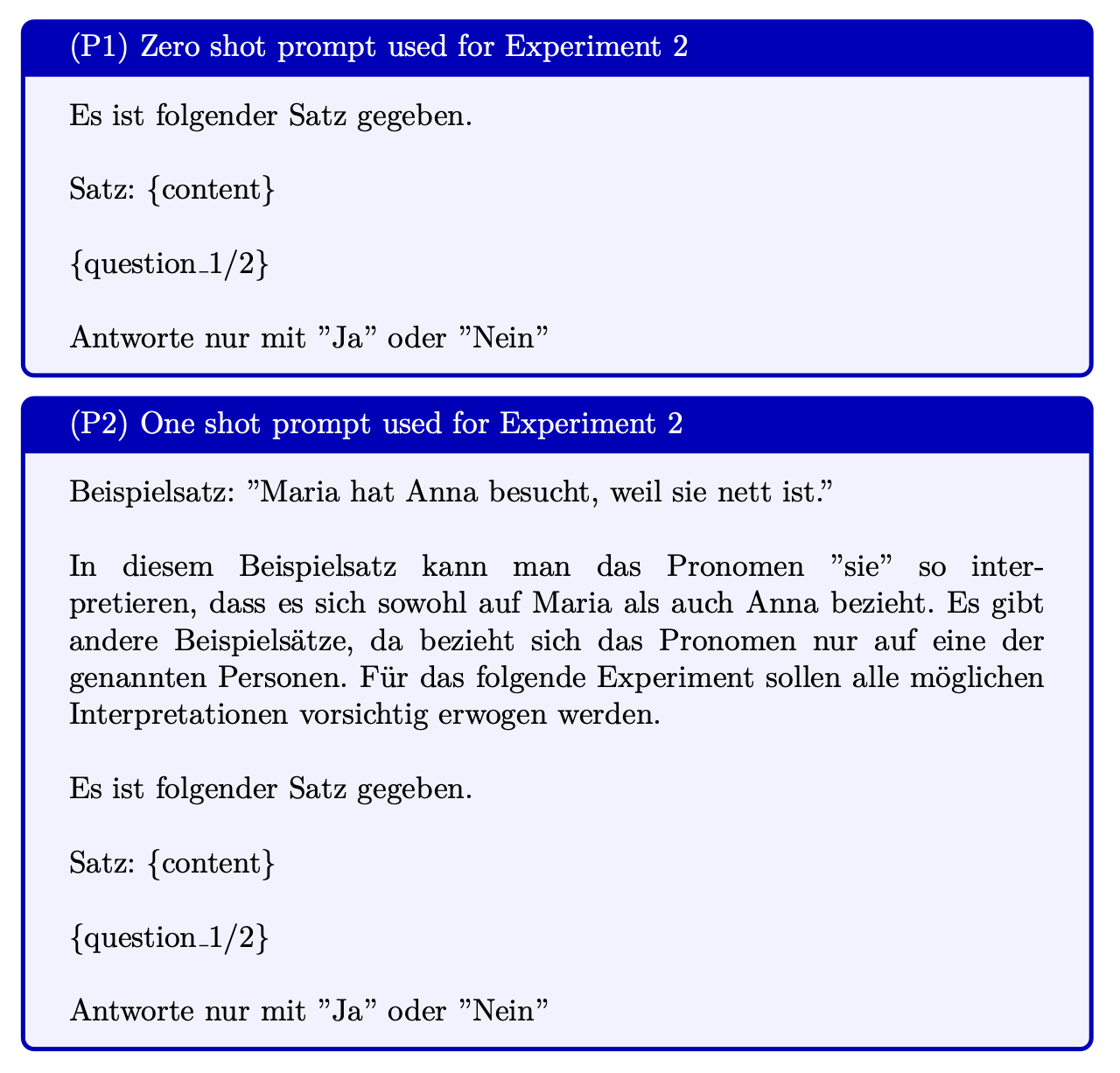

Prompt P1 was chosen for the task after some manual experimentation. Since Experiment 2 from (Salzmann et al., 2022) was conducted in German, German was also used for the model instructions in the prompt (Consider the Appendix for the original prompts):

The variables ’content’ and ’question’ in the prompt referred to the different conditioned sentences that belonged to the experimental items from Salzmann et al. (2022).

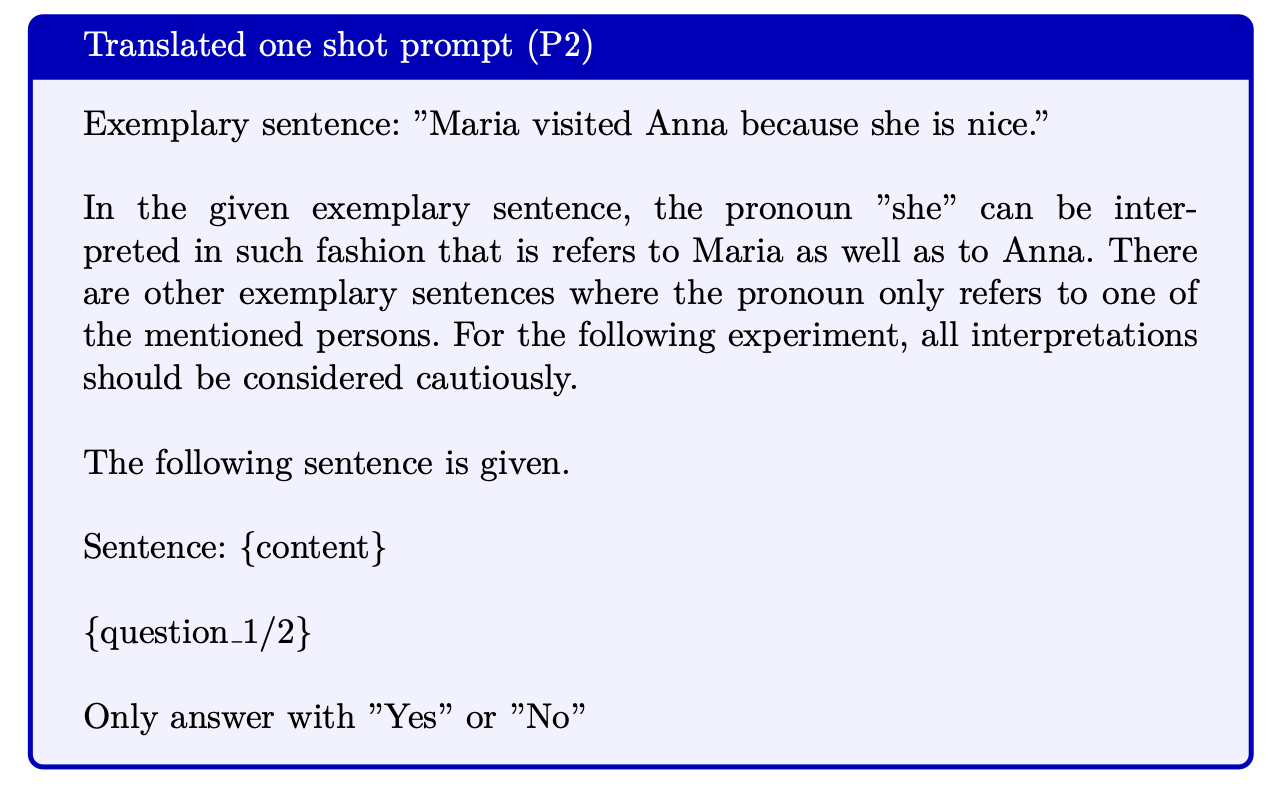

Since the participants in Experiment 2 received instructions, a second prompt P2 with a similar instruction for the large language model was used.

P2 was an instance of what is commonly known as few shot learning because GPT 3.5 Turbo received one example with an ideal solution.

4.2 Results from GPT 3.5 Turbo

The closest overall results compared to the baseline of human answers can be derived from a zero shot configuration of GPT 3.5 Turbo (Table 4). In the configuration with four iterations and a zero shot prompt, Q1 received a great share of positive answers in all conditions. Q2 was almost never positively answered with phrases that contained the R-expression as an object (Condition a-d). The adjunct position led to some greater variability though (21.1% and 35.9% positive answers). For Q2, GPT 3.5 Turbo provided mostly more positive answers than humans when queried with subject phrases, with one exception (Condition e). For subjects, GPT 3.5 Turbo’s proportions of answers differ to those from humans up to 9,4%. The four times iterated one shot configuration led to a lot of positive answers for both Q1 and Q2 except for those cases where the R-expression was contained in an argument within an object phrase (Condition a and b). Again, Condition e was slightly less positively answered than the other subject conditions. The configurations with only two iterations followed the trend of both previously mentioned configurations. The configuration with a zero shot prompt and two iterations led to results which are even closer to the human baseline than the same prompt four times iterated. The greatest difference to the human baseline for the zero shot configurations can be noticed in Condition b with a difference of 35.1% and 34.3%.

Table 4: Proportion of GPT 3.5 Turbo’s positive answers, using zero and one shot prompts with 4 and 2 iterations of all items from Experiment 2 (the conditions are the same as those in Table 1)

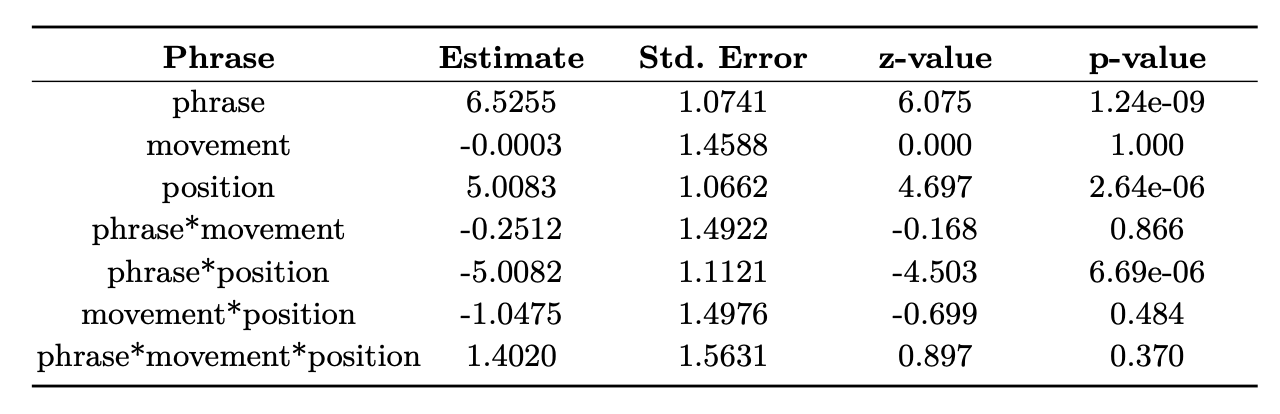

Following Salzmann et al. (2022), I fit a generalized linear mixed model with the data from the zero shot configuration after four iterations. I chose this configuration because its amount of data points resembles the amount from Experiment 2 in Salzmann et al. (2022). The items were again considered as random effects. As with the models from Salzmann et al. (2022), the baseline of Phrase was ’object’ and for Position ’argument’. Similarly, two baselines for Movement were used to account for the differences between ’in situ’ (Model 3) and ’moved’ (Model 4). I report the results in Table 5 and 6.

Table 5: Generalized linear mixed model results from the zero shot configuration with four iterations (Model 3)

Table 6: Generalized linear mixed model results from the zero shot configuration with four iterations (Model 4)

With Model 3, an effect of Phrase can be observed for the levels ’in situ’ and ’argument’ from Movement and Position with z = 5.844, p < 0.001 confirming H1 from Experiment 2. The same effect is observed with Model 4 where Phrase leads to z = 6.075, p < 0.001. If the interpretation of the LLM results were to follow Salzmann et al. (2022), the effect of Phrase in either generalized linear mixed model with ’in situ’ as well as ’moved’ as baseline for Movement would imply the acceptance of H2(a). However, no effect of Movement nor an interaction of Movement in the other levels is observed in Model 3 and 4, rejecting H2(b). As H2(a) appears to be dependent on Movement, it is questionable whether H2(a) can be accepted when no noticeable effect of Movement is given. Salzmann et al. (2022) predicted an effect of Position if H2(a) is rejected. Precisely, this effect is observed in Model 3/4 with z = 3.705,p = 0.001 and z = 4.697,p < 0.001, that is, where the appearance of the R-expression in either an argument or an adjunct position makes a difference. Position also interacts with Phrase in both models.

5 Discussion of LLMs in linguistic research

The implications of the results as well as the methodical approach presented in this contribution appear to be so extensive that I will only provide a few thoughts in this section.

5.1 Interpretation of results

To begin with, the results from the experiment with GPT 3.5 Turbo as well as with human participants clearly indicate the presence of Principle C (hypothesis H1). Generally, questions of type Q2 were answered in such a fashion that the pronoun in the given example was only referring to the corresponding R-expression from the main clause whenever the second R-expression was part of an embedded object. An increase of positive proportions for Q2 is noticed when the second R-expression is part of an embedded subject phrase.

The disagreement between the LLM and human responses with respect to hypothesis H2(a&b) aggravates the question of whether reconstruction is part of processing sentences with Principle C. While the results from 32 participants indicate an effect of movement which Salzmann et al. (2022) interpret as possible evidence for reconstruction, that is, the application of Principle C in Syntax under the assumption that the pre-moved position is the key to its force, the large language model responses do not indicate such an effect. This raises multiple questions: Does a language model operate differently when applying Principle C than human beings? Is movement the right variable for investigating reconstruction? Do human beings really reconstruct? Salzmann et al. (2022, 607) also question their results from Experiment 2: ”How can the finding that the base position plays a role (pointing toward reconstruction) be reconciled with the finding that the surface position also matters (speaking against reconstruction)?” In other words, an effect of movement is attested, but it is difficult to reconcile with the fact that the surface position of the moved phrase also influences the participants’ interpretations. Given that the proportions of answers from their experiment does not lead to clear numbers, and that the authors attempt to avoid a logic of arbitrary thresholds (e.g., share of proportions below 20% should be considered as noise), they reject strong reconstruction with Principle C as the governing factor of coreference in German A ́-movements. The LLM’s results appear to confirm this conclusion because the LLM’s responses were not considerably influenced by movement.

The effect of position (hypothesis H3) is confirmed with the LLM. The results from 32 participants indicated that the adjunct and argument position were not treated differently and for that matter H3 was rejected in Salzmann et al. (2022). However, the LLM corroborates the established view (Lebeaux, 1991) that there is an asymmetry between the argument and adjunct position as Position led to a significant effect in the generalized linear mixed model that was fit with the LLM’s responses.

5.2 The use of LLMs in linguistic research

The idea of using models to simulate responses in linguistic experiments has been previously explored with smaller language models based on recurrent neural networks (RNNs), as seen in Linzen et al. (2016) and Futrell et al. (2019). This work culminated in the development of SyntaxGym, a platform led by Jennifer Hu, Jon Gauthier, Ethan Wilcox, Peng Qian, and Roger Levy at the MIT Computational Psycholinguistics Laboratory. SyntaxGym’s objective is to evaluate how well deep neural network models align with human intuitions about grammatical phenomena. Transformer-based models were later integrated into the platform. Additionally, research comparing neural language models with human responses in psycholinguistic studies is presented in Wilcox et al. (2021), while Li et al. (2024) examine the alignment between humans and large language models in processing garden-path sentences. Haider (2023) offers a qualitative perspective on potential applications of large language models in linguistic research. Nevertheless, the scientific validity of using language models in this context remains a topic of debate.

At the outset, we might wonder: ”Do large language models (LLMs) constitute a computational account of how humans process language?” (Blank, 2023, 987) For Blank, this question is inherently linked to how the mind is understood: Does it work on symbolic or distributed structures? I cannot discuss this question in more detail here. But I would like to suggest a pragmatic affirmation of the initial question: Let us assume that current LLMs can serve as an account of how humans process language. As it appears to me, we would then find ourselves in a situation that might be abstracted as follows:

Syntax Theory ← Human Language → Large Language Model

where both, syntax theories and LLMs, approximate the workings and patterns of human language. The former does so based on symbolic rules, whereas the latter is running on ”distributed patterns of activation across hidden units within LLMs (i.e., the ‘neurons’ of the LLM)” (Blank, 2023, 987). If we do research in linguistics, for example syntax, by using LLMs in experiments, I believe that we would look at the following situation:

Syntax Theory ← Large Language Model ← Human Language

This line of research seems acceptable, if we agree that the LLM is good enough in approximating human language, although it would certainly have substantial differences compared with human participants (e.g., the LLM’s linguistic capacity is not grounded in a ”human-like trajectory of language acquisition” (Blank, 2023, 988)).

The application of large language models (LLMs) in empirical syntax, as proposed in Chapter 4, serves as further evidence that they can enhance theory testing. In general, this research approach aims not only to simulate human language utterances using LLMs for specific research purposes but also to generate linguistic judgments (e.g., by prompting ”Yes” or ”No” responses from an LLM). The data produced by LLMs could then be used to support linguistic theories, such as providing evidence for the existence of Principle C in German.

If this approach proves successful and scientifically valid, using LLM simulations could significantly streamline linguistic research. Researchers would no longer need to recruit participants, create filler items for distraction, or rely on laboratory settings for experiments. Instead, a syntactician could simply return to her armchair, testing theories with a computer and proper access to an LLM.

However, a significant dependence on the underlying LLMs would also ensue. If the LLM does not represent human language appropriately, its errors would be propagated and syntactic theories might be accepted or rejected based on the LLM’s incomplete representation of human language. The decision to split up the questions Q1 and Q2 for separate queries to reduce the complexity of the task (also consider the one-shot prompt that rather ”confused” the LLM) indicates that GPT 3.5 Turbo is still processing language differently than human beings. This suggests, if an LLM is used in syntactic research, we must consider its limits and capacities thoroughly before we deploy it.

5.3 The implication of linguistic experiments for LLMs

Deploying LLMs in linguistic research would also help with understanding and possibly improving LLMs. Begus et al. (2023) argue that ”testing complex metalinguistic abilities of large language models is now a possible line of inquiry” and ”that the results of such tests can provide valuable insights into LLMs’ general metacognitive abilities.” (Begus et al., 2023) For example, Begus et al. (2023) created several tests to specifically check how GPT 4 provides formal and theoretical answers to syntactic, semantic, and phonological questions. In similar vain, Wilson et al. (2023) used linguistically inspired tests to investigate how LLMs process argument structures. In particular, they investigated if LLMs can generalize from argument patterns that are recognizable in different contexts. They report that RoBERTa, BERT, and DistilBERT fail some of their tests because they observed that these models are prone to errors ”based on surface level properties like the relative linear order of corresponding elements.” (Wilson et al., 2023, 1391) (This could be a reason why GPT 3.5 Turbo did not show signs of reconstruction. ) Therefore, such experiments would not only help us with understanding the LLMs’ limits, but could also be used for improving future models.

The deployment of GPT 3.5 Turbo for pronoun resolution in contexts that are covered by Principle C has shown that few shot learning does not improve the model’s answers. The ambiguous example given in the instruction rather nudged the LLM into accepting more syntactically incorrect interpretations than without. This suggests that few-shot learning may not always be helpful for LLMs if ambiguous phrases are at stake. Furthermore, GPT 3.5 Turbo was generally sensitive to the prompt. An even shorter wording for the task led in manual experimentation to diminished results. This finding corroborates the recent discussion of LLM’s fickleness by Fourrier et al. (2024).

Project scripts

The scripts used for the experiments can be found here: https://github.com/omseeth/using_llms_for_syntactic_research

Appendix

I would like to thank Martin Salzmann for providing me with the materials and experimental data from Salzmann et al. (2022).

Bibliography

Adger, D., Drummond, A., Hall, D., and van urk, C. (2017). Is there condition c reconstruction? In Lamont, A. and Tetzloff, K., editors, Nels 47: Proceedings of the forty-seventh annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, volume 1, pages 21–30. GLSA.

Bates, D. M., Kliegl, R., Vasishth, S., and Baayen, H. (2015). Parsimonious mixed models. arXiv: Methodology.

Begus, G., Dabkowski, M., and Rhodes, R. (2023). Large linguistic models: An- alyzing theoretical linguistic abilities of llms. arXiv: Computation and Language.

Blank, I. A. (2023). What are large language models supposed to model? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 27(11):987–989.

Bruening, B. and Khalaf, E. A. (2018). No argument–adjunct asymmetry in reconstruction for binding condition c. Journal of Linguistics, 55:247–276. Citko, B. (1993). Deletion Under Identity in Relative Clauses. Proceedings of the North Eastern Linguistic Society (NELS), 31:131–145.

Fourrier, C., Louf, R., and Kurt, W. (2024). Improving prompt consistency with structured generations. https://huggingface.co/blog/evaluation-structured-outputs.

Futrell, R., Wilcox, E., Morita, T., Qian, P., Ballesteros, M., and Levy, R. (2019). Neural language models as psycholinguistic subjects: Representations of syntactic state. In Burstein, J., Doran, C., and Solorio, T., editors, Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 32–42, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Haider, H. (2023). Is chat-gpt a grammatically competent informant? ling-buzz/007285.

Huang, J. (1993). Reconstruction and the Structure of VP: Some Theoretical Consequences. Linguistic Inquiry, 24(1):103–138.

Lebeaux, D. (1991). Relative Clauses, Licensing, and the Nature of the Derivation. Perspectives on Phrase Structure: Heads and Licensing, 25:209–239.

Li, A., Feng, X., Narang, S., Peng, A., Cai, T., Shah, R. S., and Varma, S. (2024). Incremental comprehension of garden-path sentences by large language models: Semantic interpretation, syntactic re-analysis, and attention.

Linzen, T., Dupoux, E., and Goldberg, Y. (2016). Assessing the ability of LSTMs to learn syntax-sensitive dependencies. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 4:521–535.

Salzmann, M., Wierzba, M., and Georgi, D. (2022). Condition C in German A-movement: Tackling challenges in experimental research on reconstruction. Journal of Linguistics, 59(3):577–622.

Stockwell, R., Meltzer-Asscher, A., and Sportiche, D. (2021). There is reconstruction for condition c in english questions. In Farinelly, A. and Hil, A., editors, Nels 51: Proceedings of the fifty-first annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, volume 2, pages 205–214. GLSA.

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L. u., and Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Guyon, I., Luxburg, U. V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., and Garnett, R., editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 30. Curran Associates, Inc.

Wilcox, E., Vani, P., and Levy, R. (2021). A targeted assessment of incremental processing in neural language models and humans. In Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W., and Navigli, R., editors, Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 939–952, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Wilson, M., Petty, J., and Frank, R. (2023). How abstract is linguistic generalization in large language models? experiments with argument structure. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 11:1377–1395.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: