Research Directions in Multimodal Chain-of-Thought (MCoT) with Sketching

Abstract This article explores adding sketching to Multimodal Chain-of-Thought (MCoT) reasoning to enhance AI capabilities. It reviews current methods, identifies key gaps such as the lack of sketch-rationale datasets, and proposes advancing the field through targeted data collection, unified multimodal models, and reinforcement learning. Applications span education, interactive agents, and embodied AI. Ethical considerations include mitigating cultural bias, and visual misrepresentation in generated sketches.

1 Introduction

Drawing and sketching are cognitive tools that humans use not only to express and communicate thoughts, but also to generate new ones [6]. For this matter, we would like to equip any intelligent system with the same ability to improve and help it communicate its reasoning. First steps in this direction have been proposed within the field of Multimodal Chain-of-Thought (MCoT) where reasoning steps are enriched with data from different modalities, such as visuals. Therefore, future research on sketching should advance the design of MCoT reasoning strategies. Improving Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) that perform such cross-modal reasoning is also relevant.

The present text outlines the motivation why sketching should be incorporated into CoT in Section 2. Several related works that use images and even sketches to aid models in reasoning are introduced in Section 3. Finally, Section 4 proposes directions for future research: a new dataset combining sketches with reasoning chains, advancements of unified MLLMs for MCoT, in particular with diffusion models, as well as the usage of reinforcement learning for existing MCoT approaches, such as rewards with Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) [9] and Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) [28], both for textual and visual reasoning.

2 Motivation to incorporate drawing capabilities into AI

Humans express and communicate ideas visually through drawing and sketching, which is a quick and loose form of drawing. Drawing is a representation of thought, but also an activity that can support ongoing cognition [6]. Drawing and sketching precede writing: The first documented drawings date back as far as 64,000 years [10]. For that reason, Fan et al. [6] argue that drawing is one of the most enduring and versatile cognitive tools from which humans have benefited.

One explanation for the power of drawing and sketching can be derived from cognitive enhancement and offloading strategies. According to Morrison and Richmond [21], technologies are used as external memories, facilitating other tasks by freeing up memory. Similarly, Osiurak et al. [24] show that tools such as maps can extend human’s cognitive abilities.

Given the relevance of drawing and sketching for human thought, expression, and communication, we would want to equip any AI with the capability to also use this tool to advance and share its own ideas. Sketching can not only be a window into how AI models process information, but it is fair to assume that it can also support their reasoning.

Reasoning in large language models (LLMs) has been greatly improved with in-context learning (ICL) [20] and Chain-of-Thought (CoT) techniques [23, 34]. ICL helps models with additional information added to the input to find appropriate responses for a given task. With CoT, the contextual information is specifically extended by a simulation of human reasoning steps, where a task is divided into subtasks for which intermediate solutions are given so that the model can derive its final answer from them. This can be achieved by eliciting reasoning through prompting, as with ’think step-by-step’ prompts (Zero-Shot-CoT [15]), or by providing the model with an explicit reasoning demonstration (also called a rationale) for a given problem (Few-Shot-CoT [34]).

CoT has been extended with multimodal information [32, 33] where models receive more than text to guide them toward a correct answer. This information can consist of visual, auditory, or spatio-temporal data. Sketches would be additional visual information. They could also help models to offload complex tasks and retain intermediate memories, for example, of subtasks. Therefore, an implementation of the capability to sketch in order to enhance models’ reasoning abilities should expand existing research in MCoT. A detailed account of MCoT is given in Appendix A.

3 Related work

Several recent approaches explore MCoT reasoning, though most do not fully integrate sketch generation into the reasoning process.

Zhang et al. [42] propose a two-stage framework for multiple-choice reasoning for text and image inputs where a FLAN-AlpacaBase model [30, 44] first produces a rationale, then derives the answer. Fusing text and image features from the input improves performance, but the system cannot generate new visual content. This limits applicability to reasoning scenarios that benefit from active visual exploration, such as diagram construction in geometry or mechanical design tasks.

Meng et al. [19] extend CoT by having an LLM produce symbolic sketch-like diagrams (e.g., with SVG), rendered into images and re-encoded for reasoning. Their ’think image by image’ approach helps, for example, with geometric tasks. However, this gain comes at the cost of operational complexity: the pipeline depends on separate LLMs, rendering engines, and encoders, creating latency and integration challenges. Unified MLLMs avoid such fragmentation and may better support generalization by learning a shared latent space for both text and sketches.

In contrast to the previous two approaches, Liao et al. [16] fine-tune unified MLLMs (SEED-LLaMA [7] and SEED-X [8]) on their ImageGen-CoT dataset. Reasoning steps of their models precede image generation. Test-Time Scaling is applied to select better outputs. While they demonstrate high-quality image generation, their evaluation focuses on aesthetics and relevance rather than measurable reasoning improvement. For reasoning-centric applications, visual fidelity without explicit reasoning gains may be insufficient.

Hu et al. [11] and Vinker et al. [31] develop agentic strategies (Sketchpad, Sketchagent) where models like GPT-4o [13] or Claude3.5-Sonnet [3] can decide to produce or modify sketches during problem-solving by leveraging external vision models, Python or a domain-specific language (DSL) for sketches. Models with Sketchpad iterate over a ’thought’, ’action’ (to inject sketches), and ’observation’ pattern. With this approach, Hu et al. [11] show that allowing models to decide to insert sketches during reasoning leads to notable performance gains. However, the framework relies on external vision models to rather enhance or dissect images and a Python sketch representation, which may not capture the nuances of freehand or abstract sketches common in human reasoning.

A truly multimodal approach for sketches would not use Python or DSLs to ’implicitly’ generate figures that the model ingests as textual input. However, few multimodal datasets that combine visuals with rationales exist. While QuickDraw [14] provides scale and diversity in sketch data, its lack of accompanying rationales prevents multimodal alignment learning. ScienceQA [18] and ImageGen-CoT [16] offer strong rationale-image pairs, but the absence of sketches means they primarily serve full-image reasoning rather than schematic reasoning. This gap suggests that the field currently lacks a dataset that balances sketch simplicity with reasoning, a pairing that could uniquely advance MCoT.

Overall, existing MCoT work shows that visual information, including sketches, can aid reasoning. However, limitations remain: most systems either consume but do not create sketches, focus on image quality rather than reasoning improvement, or require orchestration of multiple models instead of unified generation. Furthermore, appropriate datasets with sketches in combination with rationales are lacking.

4 Future research for MCoT with sketching

Given the power of visual information for reasoning tasks, as shown by [42, 19, 16, 11], some of the shortcomings of existing MCoT approaches can be addressed to better incorporate sketching in future research.

4.1 Creating a new MCoT sketch dataset

To facilitate the training of MLLMs, the lack of an appropriate dataset with sketching and rationales is a limitation.

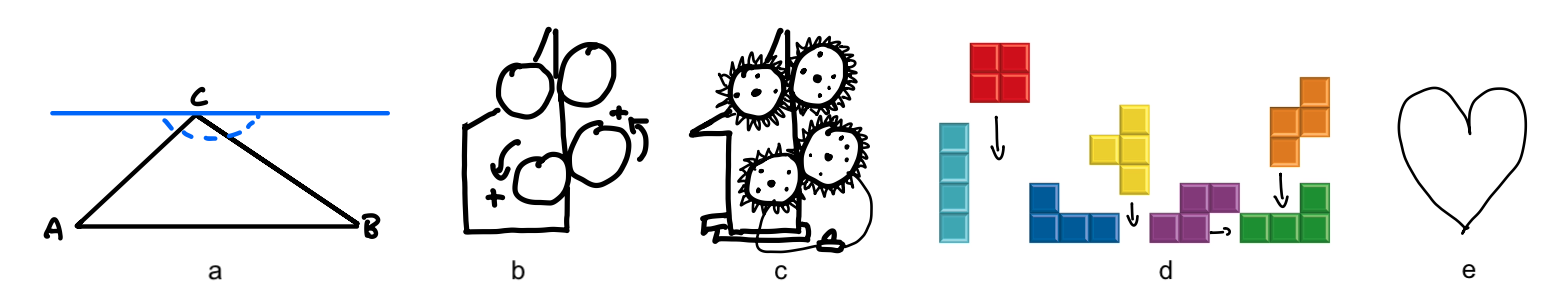

Sketch data should be gathered and grouped within different categories, depending on the downstream task (consider Figure 1). In experimental studies with humans, Huey et al. [12] point out that drawings differ according to their intended goal: visual explanations by the participants emphasized moving and interactive parts, while their visual depictions focused on salient features. Hu et al. [11] show that adding auxiliary lines to geometric figures helps multimodal models such as GPT-4o to infer correct answers about these figures. Fan et al. [6] highlight that not all drawings are faithful depictions, but can also be abstractions whose meanings are conveyed by cultural conventions.

Figure 1: Different types of sketches and drawings: (a) depicts a geometric form that has an auxiliary line, (b) emphasizes moving parts of a machine, (c) depicts the same machine in more detail, (d) represents figures from tetris whose next moves are indicated with arrows, (e) is a conventional sketch of a heart that does not resemble actual human hearts.

To integrate sketches into a CoT, training data should not only consist of images of drawings and sketches, but combine these with textual rationales. This would enable multimodal alignment between visual and linguistic reasoning steps. A typical template for this data could consist of instruction I, query Q, rationale R, and answer A where we could further divide R into ’thought’, ’sketch’, and ’observation’ with respective special tokens to guide the model, loosely following Hu et al. [11]. An example template is given in Appendix B. Since ScienceQA and ImageGen-CoT already pair images with rationales, they could be extended with sketches to strengthen visual-textual alignment for their tasks.

4.2 Advancing MCoT with unified MLLMs

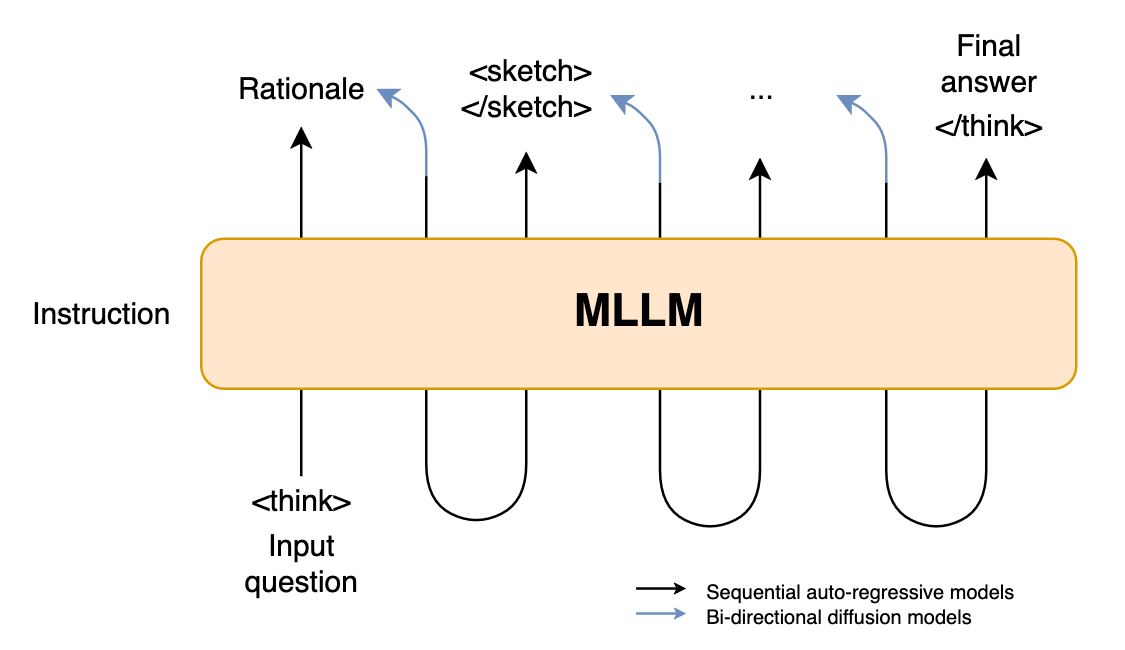

To avoid multi-model orchestration and to leverage potential transfer-learning effects, further advancing reasoning of MLLMs with sketches is a promising direction. However, there exist only a few MLLMs [39, 43, 42, 29] that can potentially handle sketch-to-text as well as text-to-sketch tasks within a unified architecture (consider Figure 2). The majority of current approaches such as Sketchpad pair VLMs such as Flamingo [2], PaLM-E [5], LLAVA [17], GPT-4o [13], or Claude3-Opus and Claude3.5-Sonnet [3] with text-to-image models.

Unified MLLMs can be divided into autoregressive (AR) and diffusion-based MLLMs. For example, CM3Leon [39] from Meta is a Transfomer-based AR decoder that can generate both text and images. It is built on the CM3 model [1]. CM3Leon has been trained on text-guided image editing, image- to-image grounding tasks where visual features can be derived from images, and text-to-image generations.

Swerdlow et al. [29] introduce a unified multimodal discrete diffusion model (UniDisc). While the model’s architecture consists of a Transformer (bidirectional) decoder, its training goal is not to auto-regressively predict the next tokens in a sequential manner (e.g., left to right for text or top to bottom for image patch rasters), but to predict the distribution of tokens via a denoising process that allows parallel predictions as well as later refinements. The training of UniDisc is realized with a denoising process of corrupted inputs (masking). In contrast to continuous diffusion models, Swerdlow et al. [29] use discrete noising and denoising for both images and texts. Swerdlow et al. [29] show that UniDisc outperforms the same architecture without a diffusion objective with respect to image and text classification tasks. The model is also capable of inpainting and infilling missing parts of an input, which no AR model can do. However, these performance gains come at a cost: UniDisc requires 13.2 times longer than its AR counterpart to reach equivalent loss levels [29].

Figure 2: MCoT involving sketches with a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM). Black arrows represent sequential auto-regressive processing, while blue arrows illustrate the bidirectionality of diffusion models. The model’s reasoning is guided by special tokens, such as

Models like UniDisc provide an interesting model class for MCoT. While current diffusion language models (DLMs) might not rival AR LLMs due to training inefficiencies [29] or speed [38], the strength of multimodal DLMs in handling and generating multimodal data – as shown by Swerdlow et al. [29] – warrants further research. Their ability to inpaint and infill would be particularly helpful for amending visualizations, which is a core aspect of explanatory sketching. Research in this direction could be informed by Diffusion-of-Thought (DoT) proposed by Ye et al. [37], who fine-tune a DLM for CoT. However, diffusion models require a fixed output size. This is a challenge that needs to be addressed to allow versatile reasoning over different tasks.

4.3 Improving MCoT with Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Test-Time Scaling

Existing work on MCoT [42, 19, 16] has so far relied on supervised fine-tuning (SFT). Other work in reasoning has shown that RL leads to improvements [9, 27, 43]. Therefore, MCoT should be advanced with Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) [26], Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) [9] and Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) [28] strategies. One straight-forward application would be to use RLVR with GRPO, following Deepseek’s R1 [9], to reward accuracy (\(R_{acc}\)) and format (\(R_{format}\)) for rationales and answers based on generated sketches.

An appropriate reward for the generation of sketches could leverage AR-GRPO for autoregressive MLLMs [40]. AR-GRPO realizes rewards for the generation of images with a multi-faceted reward function that ensures (a) consistency with the textual input condition through CLIP [25] and Human Preference Score v2 [35], (b) image quality with MANIQA [36], and (c) a further realism reward through a VLM, such as Qwen2.5-VL-3B-Instruct [4]. This function is used with GRPO to improve the quality of generated images. Since the proposed rewards by Yuan et al. [40] focus on overall quality, a specific reward should be conceived for sketches. For example, a sketch can consist of a hierarchy of strokes whose meaning can be of different importance. It would be interesting to incorporate this somehow into the reward: Should sketches with a limited amount of strokes be prioritized?

In the wake of Liao et al. [16], existing MCoT could be further improved with Test-Time Scaling methods, sampling more CoTs and sketches to select the best candidates with an appropriate scoring method. This approach could also be used with agentic frameworks that pair VLMs with image generators and would not require any additional training of the models.

Beyond standard accuracy on downstream tasks, evaluation should measure how sketches contribute to the reasoning process. This includes interpretability (e.g., can a human follow the model’s reasoning with a sketch?), task completion time (one of the biggest bottlenecks because image generation requires many tokens), error localization, and robustness under noisy or incomplete inputs. Additionally, user studies could assess subjective clarity and helpfulness of generated sketches.

Impact

MLLMs with sketching would have an impact on AI in different domains. For example, agentic systems such as Auto-GUI [41] that interact with graphical user interfaces or websites could be enhanced by providing them with additional visual information with sketches. Similarly, embodied AI systems, such as EmbodiedGPT [22] whose backbone uses a combination of vision and language models that help navigate the real world, could reason about their surroundings using sketches. MLLMs for STEM education could also benefit from the ability to make their reasoning more transparent with additional drawings as proposed in Meng et al. [19]. In sum, sketching would help all reasoning models not only to enhance their thoughts, but also communicate them with more than one modality.

As with language, sketches are not neutral representations. The ability of AI systems to generate and reason with sketches introduces risks of cultural bias, visual misrepresentation, and domain-specific inaccuracies. For example, the “heart” symbol in Figure 1(e) is globally recognized in popular culture but anatomically incorrect; in medical education, reasoning over such a schematic could reinforce misconceptions. Similar issues may arise if models default to culturally specific diagrammatic conventions, omit critical features due to dataset biases, or overgeneralize from training examples.

Ethical safeguards should address the entire MCoT-with-sketching workflow. Dataset curation must ensure diversity of styles, cultural perspectives, and schematic conventions. Annotation guidelines should clarify the intended use and accuracy requirements of sketches. Model evaluation should include bias detection for visual outputs, alongside interpretability checks so users can trace how a sketch influenced reasoning.

Apendix A: MCoT foundations

Following Wang et al. [33], we can define prompt, instruction, query, answer, and rationale with \(P\) , \(I\), \(Q\), \(A\), and \(R\), which are all token sequences. A Chain-of-Thought (CoT) would be:

\begin{equation} P_{CoT} = {I, (x_1, e_1, y_1), …, (x_n, e_n, y_n)} \end{equation}

where \(x_i \in Q\) and \(y_i \in A\) are questions with corresponding answers and \(e_i \in R\) is an example rationale. The joint probability of generating an answer A and a rationale R given the prompt \(P_{CoT}\) and a query \(Q\) would be [33]:

\begin{equation} p(A, R |P_{CoT}, Q) = p(R |P_{CoT}, Q) \cdot p(A |P_{CoT}, Q, R) \end{equation}

where the model should output rationale \(R\) with the tokens \(r_1, ..., r_i\) before arriving at the answer \(A\) consisting of the tokens \(a_1, ..., a_i\). The goal in training a reasoning model \(F\) is to jointly maximize the likelihood of equation (2).

Finally, all components \(P\), \(Q\), \(A\), and \(R\) can be enriched with multimodal information \(\mathcal{M}\). For example with MCoT, a rationale \(R\) should handle \(\mathcal{M}\) input and generate multimodal information (e.g., a sketch) as well as text \(T\), that is, \(R\in\{M, M\oplus T\}\) [33].

Appendix B: MCoT template

{ "instruction": "Find proofs for geometry problems.", "query": "Prove the angles of ABC provided in the attached image sum to 180. <image> VT_011 VT_115 VT_563 VT_101 ... VT_909 </image>", "rationale": "<think> I need to figure out how ABC are related in the image. The image shows a triangle. I need to prove that the angles of the triangle sum to 180. To find an answer, I draw a triangle: Let's call it ABC. <sketch> VT_421 VT_105 VT_983 VT_002 ... VT_778 </sketch> I extend the sides from A to B, from A to C, and from B to C. <sketch> VT_421 VT_105 VT_983 VT_001 ... VT_708 </sketch> I draw a line parallel to AB through point C. <sketch> VT_420 VT_105 VT_983 VT_001 ... VT_718 </sketch> <observe> The angles at point C created by the parallel line correspond to the interior angles at points A and B. When I add those angles up, they form a straight line at point C, which measures 180. Since those angles correspond exactly to the three interior angles of the triangle, the sum of the interior angles is 180. </observe> This proof follows from the alternate interior angles theorem. </think>", "answer": "The alternate interior angles theorem shows that all angles at point C created by the parallel line sum to 180. They further correspond to the interior angles at points A and B. Therefore, the angles of ABC provided in the attached image sum to 180." }

MCoT template with instruction \(I\), query \(Q\), rationale \(R\), and answer \(A\) where \(R\) is further divided into “thought”, “sketch”, and “observation” with respective special tokens to guide the model. VT_n tokens correspond to image tokens.

Bibliography

[1] Aghajanyan, A., Huang, P.-Y. B., Ross, C., Karpukhin, V., Xu, H., Goyal, N., Okhonko, D., Joshi, M., Ghosh, G., Lewis, M., and Zettlemoyer, L. (2022). Cm3: A causal masked multimodal model of the internet. ArXiv, abs/2201.07520.

[2] Alayrac, J.-B., Donahue, J., Luc, P., Miech, A., Barr, I., Hasson, Y., Lenc, K., Mensch, A., Millican, K., Reynolds, M., Ring, R., Rutherford, E., Cabi, S., Han, T., Gong, Z., Samangooei, S., Monteiro, M., Menick, J., Borgeaud, S., Brock, A., Nematzadeh, A., Sharifzadeh, S., Binkowski, M., Barreira, R., Vinyals, O., Zisserman, A., and Simonyan, K. (2022). Flamingo: a visual language model for few-shot learning. ArXiv, abs/2204.14198.

[3] Anthropic (2024). The claude 3 model family: Opus, sonnet, haiku.

[4] Bai, S., Chen, K., Liu, X., Wang, J., Ge, W., Song, S., Dang, K., Wang, P., Wang, S., Tang, J., Zhong, H., Zhu, Y., Yang, M., Li, Z., Wan, J., Wang, P., Ding, W., Fu, Z., Xu, Y., Ye, J., Zhang, X., Xie, T., Cheng, Z., Zhang, H., Yang, Z., Xu, H., and Lin, J. (2025). Qwen2.5-vl technical report. ArXiv, abs/2502.13923.

[5] Driess, D., Xia, F., Sajjadi, M. S. M., Lynch, C., Chowdhery, A., Ichter, B., Wahid, A., Tompson, J., Vuong, Q. H., Yu, T., Huang, W., Chebotar, Y., Sermanet, P., Duckworth, D., Levine, S., Vanhoucke, V., Hausman, K., Toussaint, M., Greff, K., Zeng, A., Mordatch, I., and Florence, P. R. (2023). Palm-e: An embodied multimodal language model. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

[6] Fan, J. E., Bainbridge, W. A., Chamberlain, R., and Wammes, J. D. (2023). Drawing as a versatile cognitive tool. Nature Reviews Psychology, 2(9).

[7] Ge, Y., Zhao, S., Zeng, Z., Ge, Y., Li, C., Wang, X., and Shan, Y. (2023). Making llama see and draw with seed tokenizer. ArXiv, abs/2310.01218.

[8] Ge, Y., Zhao, S., Zhu, J., Ge, Y., Yi, K., Song, L., Li, C., Ding, X., and Shan, Y. (2024). Seed-x: Multimodal models with unified multi-granularity comprehension and generation. ArXiv, abs/2404.14396.

[9] Guo, D., Yang, D., Zhang, H., Song, J.-M., Zhang, R., Xu, R., Zhu, Q., Ma, S., Wang, P., Bi, X., Zhang, X., Yu, X., Wu, Y., Wu, Z. F., Gou, Z., Shao, Z., Li, Z., Gao, Z., Liu, A., Xue, B., Wang, B.-L., Wu, B., Feng, B., Lu, C., Zhao, C., Deng, C., Zhang, C., Ruan, C., Dai, D., Chen, D., Ji, D.-L., Li, E., Lin, F., Dai, F., Luo, F., Hao, G., Chen, G., Li, G., Zhang, H., Bao, H., Xu, H., Wang, H., Ding, H., Xin, H., Gao, H., Qu, H., Li, H., Guo, J., Li, J., Wang, J., Chen, J., Yuan, J., Qiu, J., Li, J., Cai, J., Ni, J., Liang, J., Chen, J., Dong, K., Hu, K., Gao, K., Guan, K., Huang, K., Yu, K., Wang, L., Zhang, L., Zhao, L., Wang, L., Zhang, L., Xu, L., Xia, L., Zhang, M., Zhang, M., Tang, M., Li, M., Wang, M., Li, M., Tian, N., Huang, P., Zhang, P., Wang, Q., Chen, Q., Du, Q., Ge, R., Zhang, R., Pan, R., Wang, R., Chen, R. J., Jin, R., Chen, R., Lu, S., Zhou, S., Chen, S., Ye, S., Wang, S., Yu, S., Zhou, S., Pan, S., Li, S. S., Zhou, S., Wu, S.-K., Yun, T., Pei, T., Sun, T., Wang, T., Zeng, W., Zhao, W., Liu, W., Liang, W., Gao, W., Yu, W.-X., Zhang, W., Xiao, W., An, W., Liu, X., Wang, X., aokang Chen, X., Nie, X., Cheng, X., Liu, X., Xie, X., Liu, X., Yang, X., Li, X., Su, X., Lin, X., Li, X. Q., Jin, X., Shen, X.-C., Chen, X., Sun, X., Wang, X., Song, X., Zhou, X., Wang, X., Shan, X., Li, Y. K., Wang, Y. Q., Wei, Y. X., Zhang, Y., Xu, Y., Li, Y., Zhao, Y., Sun, Y., Wang, Y., Yu, Y., Zhang, Y., Shi, Y., Xiong, Y., He, Y., Piao, Y., Wang, Y., Tan, Y., Ma, Y., Liu, Y., Guo, Y., Ou, Y., Wang, Y., Gong, Y., Zou, Y.-J., He, Y., Xiong, Y., Luo, Y.-W., mei You, Y., Liu, Y., Zhou, Y., Zhu, Y. X., Huang, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, Y., Zhu, Y., Ma, Y., Tang, Y., Zha, Y., Yan, Y., Ren, Z., Ren, Z., Sha, Z., Fu, Z., Xu, Z., Xie, Z., guo Zhang, Z., Hao, Z., Ma, Z., Yan, Z., Wu, Z., Gu, Z., Zhu, Z., Liu, Z., Li, Z.-A., Xie, Z., Song, Z., Pan, Z., Huang, Z., Xu, Z., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, Z. (2025). Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. ArXiv, abs/2501.12948.

[10] Hoffmann, D. L., Standish, C. D., García-Diez, M., Pettitt, P. B., Milton, J. A., Zilhão, J., Alcolea-González, J. J., Cantalejo-Duarte, P., Collado, H., de Balbín, R., Lorblanchet, M., Ramos- Muñoz, J., Weniger, G.-C., and Pike, A. W. G. (2018). U-th dating of carbonate crusts reveals neandertal origin of iberian cave art. Science, 359(6378):912–915.

[11] Hu, Y., Shi, W., Fu, X., Roth, D., Ostendorf, M., Zettlemoyer, L. S., Smith, N. A., and Krishna, R. (2024). Visual sketchpad: Sketching as a visual chain of thought for multimodal language models. ArXiv, abs/2406.09403.

[12] Huey, H., Lu, X., Walker, C. M., and Fan, J. (2023). Visual explanations prioritize functional properties at the expense of visual fidelity. Cognition, 236.

[13] Hurst, A., Lerer, A., Goucher, A. P., Perelman, A., Ramesh, A., Clark, A., Ostrow, A., Welihinda, A., Hayes, A., Radford, A., Mkadry, A., Baker-Whitcomb, A., Beutel, A., Borzunov, A., Carney, A., Chow, A., Kirillov, A., Nichol, A., Paino, A., Renzin, A., Passos, A., Kirillov, A., Christakis, A., Conneau, A., Kamali, A., Jabri, A., Moyer, A., Tam, A., Crookes, A., Tootoochian, A., Tootoonchian, A., Kumar, A., Vallone, A., Karpathy, A., Braunstein, A., Cann, A., Codispoti, A., Galu, A., Kondrich, A., Tulloch, A., drey Mishchenko, A., Baek, A., Jiang, A., toine Pelisse, A., Woodford, A., Gosalia, A., Dhar, A., Pantuliano, A., Nayak, A., Oliver, A., Zoph, B., Ghorbani, B., Leimberger, B., Rossen, B., Sokolowsky, B., Wang, B., Zweig, B., Hoover, B., Samic, B., McGrew, B., Spero, B., Giertler, B., Cheng, B., Lightcap, B., Walkin, B., Quinn, B., Guarraci, B., Hsu, B., Kellogg, B., Eastman, B., Lugaresi, C., Wainwright, C. L., Bassin, C., Hudson, C., Chu, C., Nelson, C., Li, C., Shern, C. J., Conger, C., Barette, C., Voss, C., Ding, C., Lu, C., Zhang, C., Beaumont, C., Hallacy, C., Koch, C., Gibson, C., Kim, C., Choi, C., McLeavey, C., Hesse, C., Fischer, C., Winter, C., Czarnecki, C., Jarvis, C., Wei, C., Koumouzelis, C., Sherburn, D., Kappler, D., Levin, D., Levy, D., Carr, D., Farhi, D., Mély, D., Robinson, D., Sasaki, D., Jin, D., Valladares, D., Tsipras, D., Li, D., Nguyen, P. D., Findlay, D., Oiwoh, E., Wong, E., Asdar, E., Proehl, E., Yang, E., Antonow, E., Kramer, E., Peterson, E., Sigler, E., Wallace, E., Brevdo, E., Mays, E., Khorasani, F., Such, F. P., Raso, F., Zhang, F., von Lohmann, F., Sulit, F., Goh, G., Oden, G., Salmon, G., Starace, G., Brockman, G., Salman, H., Bao, H.-B., Hu, H., Wong, H., Wang, H., Schmidt, H., Whitney, H., woo Jun, H., Kirchner, H., de Oliveira Pinto, H. P., Ren, ˙ H., Chang, H., Chung, H. W., Kivlichan, I., O’Connell, I., Osband, I., Silber, I., Sohl, I., Ibrahim Cihangir Okuyucu, Lan, I., Kostrikov, I., Sutskever, I., Kanitscheider, I., Gulrajani, I., Coxon, J., Menick, J., Pachocki, J. W., Aung, J., Betker, J., Crooks, J., Lennon, J., Kiros, J. R., Leike, J., Park, J., Kwon, J., Phang, J., Teplitz, J., Wei, J., Wolfe, J., Chen, J., Harris, J., Varavva, J., Lee, J. G., Shieh, J., Lin, J., Yu, J., Weng, J., Tang, J., Yu, J., Jang, J., Candela, J. Q., Beutler, J., Landers, J., Parish, J., Heidecke, J., Schulman, J., Lachman, J., McKay, J., Uesato, J., Ward, J., Kim, J. W., Huizinga, J., Sitkin, J., Kraaijeveld, J., Gross, J., Kaplan, J., Snyder, J., Achiam, J., Jiao, J., Lee, J., Zhuang, J., Harriman, J., Fricke, K., Hayashi, K., Singhal, K., Shi, K., Karthik, K., Wood, K., Rimbach, K., Hsu, K., Nguyen, K., Gu-Lemberg, K., Button, K., Liu, K., Howe, K., Muthukumar, K., Luther, K., Ahmad, L., Kai, L., Itow, L., Workman, L., Pathak, L., Chen, L., Jing, L., Guy, L., Fedus, L., Zhou, L., Mamitsuka, L., Weng, L., McCallum, L., Held, L., Long, O., Feuvrier, L., Zhang, L., Kondraciuk, L., Kaiser, L., Hewitt, L., Metz, L., Doshi, L., Aflak, M., Simens, M., laine Boyd, M., Thompson, M., Dukhan, M., Chen, M., Gray, M., Hudnall, M., Zhang, M., Aljubeh, M., teusz Litwin, M., Zeng, M., Johnson, M., Shetty, M., Gupta, M., Shah, M., Yatbaz, M. A., Yang, M., Zhong, M., Glaese, M., Chen, M., Janner, M., Lampe, M., Petrov, M., Wu, M., Wang, M., Fradin, M., Pokrass, M., Castro, M., Castro, M., Pavlov, M., Brundage, M., Wang, M., Khan, M., Murati, M., Bavarian, M., Lin, M., Yesildal, M., Soto, N., Gimelshein, N., talie Cone, N., Staudacher, N., Summers, N., LaFontaine, N., Chowdhury, N., Ryder, N., Stathas, N., Turley, N., Tezak, N. A., Felix, N., Kudige, N., Keskar, N. S., Deutsch, N., Bundick, N., Puckett, N., Nachum, O., Okelola, O., Boiko, O., Murk, O., Jaffe, O., Watkins, O., Godement, O., Campbell-Moore, O., Chao, P., McMillan, P., Belov, P., Su, P., Bak, P., Bakkum, P., Deng, P., Dolan, P., Hoeschele, P., Welinder, P., Tillet, P., Pronin, P., Tillet, P., Dhariwal, P., ing Yuan, Q., Dias, R., Lim, R., Arora, R., Troll, R., Lin, R., Lopes, R. G., Puri, R., Miyara, R., Leike, R. H., Gaubert, R., Zamani, R., Wang, R., Donnelly, R., Honsby, R., Smith, R., Sahai, R., Ramchandani, R., Huet, R., Carmichael, R., Zellers, R., Chen, R., Chen, R., Nigmatullin, R. R., Cheu, R., Jain, S., Altman, S., Schoenholz, S., Toizer, S., Miserendino, S., Agarwal, S., Culver, S., Ethersmith, S., Gray, S., Grove, S., Metzger, S., Hermani, S., Jain, S., Zhao, S., Wu, S., Jomoto, S., Wu, S., Xia, S., Phene, S., Papay, S., Narayanan, S., Coffey, S., Lee, S., Hall, S., Balaji, S., Broda, T., Stramer, T., Xu, T., Gogineni, T., Christianson, T., Sanders, T., Patwardhan, T., Cunninghman, T., Degry, T., Dimson, T., Raoux, T., Shadwell, T., Zheng, T., Underwood, T., Markov, T., Sherbakov, T., Rubin, T., Stasi, T., Kaftan, T., Heywood, T., Peterson, T., Walters, T., Eloundou, T., Qi, V., Moeller, V., Monaco, V., Kuo, V., Fomenko, V., Chang, W., Zheng, W., Zhou, W., Manassra, W., Sheu, W., Zaremba, W., Patil, Y., Qian, Y., Kim, Y., Cheng, Y., Zhang, Y., He, Y., Zhang, Y., Jin, Y., Dai, Y., and Malkov, Y. (2024). Gpt-4o system card. ArXiv, abs/2410.21276.

[14] Jonas, J., Henry, R., Takashi, K., Jongmin, K., and Nick, F.-G. (2016). The quick, draw! - a.i. experiment.

[15] Kojima, T., Gu, S. S., Reid, M., Matsuo, Y., and Iwasawa, Y. (2022). Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. ArXiv, abs/2205.11916.

[16] Liao, J., Yang, Z., Li, L., Li, D., Lin, K. Q., Cheng, Y., and Wang, L. (2025). Imagegen-cot: Enhancing text-to-image in-context learning with chain-of-thought reasoning. ArXiv, abs/2503.19312.

[17] Liu, H., Li, C., Wu, Q., and Lee, Y. J. (2023). Visual instruction tuning. ArXiv, abs/2304.08485.

[18] Lu, P., Mishra, S., Xia, T., Qiu, L., Chang, K.-W., Zhu, S.-C., Tafjord, O., Clark, P., and Kalyan, A. (2022). Learn to explain: Multimodal reasoning via thought chains for science question answering. In The 36th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).

[19] Meng, F., Yang, H., Wang, Y., and Zhang, M. (2023). Chain of images for intuitively reasoning. ArXiv, abs/2311.09241.

[20] Min, S., Lyu, X., Holtzman, A., Artetxe, M., Lewis, M., Hajishirzi, H., and Zettlemoyer, L. (2022). Rethinking the role of demonstrations: What makes in-context learning work? ArXiv, abs/2202.12837.

[21] Morrison, A. B. and Richmond, L. L. (2020). Offloading items from memory: individual differences in cognitive offloading in a short-term memory task. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 5(1):1.

[22] Mu, Y., Zhang, Q., Hu, M., Wang, W., Ding, M., Jin, J., Wang, B., Dai, J., Qiao, Y., and Luo, P. (2023). Embodiedgpt: Vision-language pre-training via embodied chain of thought. ArXiv, abs/2305.15021.

[23] Nye, M., Andreassen, A., Gur-Ari, G., Michalewski, H. W., Austin, J., Bieber, D., Dohan, D. M., Lewkowycz, A., Bosma, M. P., Luan, D., Sutton, C., and Odena, A. (2021). Show your work: Scratchpads for intermediate computation with language models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.00114.

[24] Osiurak, F., Navarro, J., Reynaud, E., and Thomas, G. (2018). Tools don’t–and won’t–make the man: A cognitive look at the future. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(5):782– 788.

[25] Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Mishkin, P., Clark, J., Krueger, G., and Sutskever, I. (2021). Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

[26] Rafailov, R., Sharma, A., Mitchell, E., Ermon, S., Manning, C. D., and Finn, C. (2023). Direct preference optimization: Your language model is secretly a reward model. ArXiv, abs/2305.18290.

[27] Ranaldi, L. and Pucci, G. (2025). Multilingual reasoning via self-training. In North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

[28] Shao, Z., Wang, P., Zhu, Q., Xu, R., Song, J.-M., Zhang, M., Li, Y. K., Wu, Y., and Guo, D. (2024). Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models. ArXiv, abs/2402.03300.

[29] Swerdlow, A., Prabhudesai, M., Gandhi, S., Pathak, D., and Fragkiadaki, K. (2025). Unified multimodal discrete diffusion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.20853.

[30] Taori, R., Gulrajani, I., Zhang, T., Dubois, Y., Li, X., Guestrin, C., Liang, P., and Hashimoto, T. B. (2023). Alpaca: A strong, replicable instruction-following model. https://crfm.stanford.edu/2023/03/13/alpaca.html.

[31] Vinker, Y., Shaham, T. R., Zheng, K., Zhao, A., Fan, J. E., and Torralba, A. (2024). Sketchagent: Language-driven sequential sketch generation. ArXiv, abs/2411.17673.

[32] Wang, Y., Chen, W., Han, X., Lin, X., Zhao, H., Liu, Y., Zhai, B., Yuan, J., You, Q., and Yang, H. (2024). Exploring the reasoning abilities of multimodal large language models (mllms): A comprehensive survey on emerging trends in multimodal reasoning. ArXiv, abs/2401.06805.

[33] Wang, Y., Wu, S., Zhang, Y., Yan, S., Liu, Z., Luo, J., and Fei, H. (2025). Multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning: A comprehensive survey. ArXiv, abs/2503.12605.

[34] Wei, J., Wang, X., Schuurmans, D., Bosma, M., Ichter, B., Xia, F., Chi, E. H., Le, Q. V., and Zhou, D. (2022). Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS ’22, Red Hook, NY, USA. Curran Associates Inc.

[35] Wu, X., Hao, Y., Sun, K., Chen, Y., Zhu, F., Zhao, R., and Li, H. (2023). Human preference score v2: A solid benchmark for evaluating human preferences of text-to-image synthesis. ArXiv, abs/2306.09341.

[36] Yang, S., Wu, T., Shi, S., Gong, S., Cao, M., Wang, J., and Yang, Y. (2022). Maniqa: Multi- dimension attention network for no-reference image quality assessment. 2022 IEEE/CVF Confer- ence on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), pages 1190–1199.

[37] Ye, J., Gong, S., Chen, L., Zheng, L., Gao, J., Shi, H., Wu, C., Jiang, X., Li, Z., Bi, W., and Kong, L. (2024). Diffusion of thought: Chain-of-thought reasoning in diffusion language models. In Neural Information Processing Systems.

[38] Ye, J., Xie, Z., Zheng, L., Gao, J., Wu, Z., Jiang, X., Li, Z., and Kong, L. (2025). Dream 7b.

[39] Yu, L., Shi, B., Pasunuru, R., Muller, B., Golovneva, O. Y., Wang, T., Babu, A., Tang, B., Karrer, B., Sheynin, S., Ross, C., Polyak, A., Howes, R., Sharma, V., Xu, P., Tamoyan, H., Ashual, O., Singer, U., Li, S.-W., Zhang, S., James, R., Ghosh, G., Taigman, Y., Fazel-Zarandi, M., Celikyilmaz, A., Zettlemoyer, L., and Aghajanyan, A. (2023). Scaling autoregressive multi-modal models: Pretraining and instruction tuning. ArXiv, abs/2309.02591.

[40] Yuan, S., Liu, Y., Yue, Y., Zhang, J., Zuo, W., Wang, Q., Zhang, F., and Zhou, G. (2025). Ar-grpo: Training autoregressive image generation models via reinforcement learning.

[41] Zhang, Z. and Zhang, A. (2023). You only look at screens: Multimodal chain-of-action agents. ArXiv, abs/2309.11436.

[42] Zhang, Z., Zhang, A., Li, M., Zhao, H., Karypis, G., and Smola, A. J. (2023). Multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning in language models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res., 2024.

[43] Zhao, J., Wei, X., and Bo, L. (2025). R1-omni: Explainable omni-multimodal emotion recognition with reinforcement learning. ArXiv, abs/2503.05379.

[44] Zheng, L., Chiang, W.-L., Sheng, Y., Zhuang, S., Wu, Z., Zhuang, Y., Lin, Z., Li, Z., Li, D., Xing, E. P., Zhang, H., Gonzalez, J. E., and Stoica, I. (2023). Judging llm-as-a-judge with mt-bench and chatbot arena. ArXiv, abs/2306.05685.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: