Multimodal Reasoning to Solve the ARC-AGI Challenge

Abstract This article examines approaches to the Abstract Reasoning Corpus (ARC-AGI), a benchmark of human-like reasoning. While symbolic program synthesis and transductive neural methods complement each other, both are constrained by sequential, language-based representations. I contribute by (1) critically reviewing these methods, (2) drawing on cognitive science to show that reasoning can extend beyond language, and (3) outlining research directions for multimodal models that integrate visual and linguistic reasoning. By framing multimodality as essential for ARC, the article highlights a path toward more flexible and human-like AI.

1 Introduction

Artificial intelligence has made remarkable progress in domains such as language understanding or pattern recognition. Yet, the quest to develop systems that demonstrate the kind of flexible, general reasoning observed in humans remains unresolved. The Abstract Reasoning Corpus (ARC-AGI) [11] was designed to probe this gap, presenting tasks that resist memorization and instead reward adaptive reasoning and generalization. These puzzles, simple for most humans yet challenging for current AI models, provide a lens through which to examine whether AI can capture the cognitive priors underlying human intelligence.

This article investigates how different reasoning paradigms – symbolic program synthesis, transductive neural predictions, and multimodal extensions – can be combined to tackle the ARC-AGI challenge. Recent advances have demonstrated the complementarity of inductive and transductive approaches [28], suggesting that no single style of reasoning suffices for the diversity of problems embodied in ARC. Building on these insights, I argue that expanding beyond purely linguistic reasoning toward multimodal architectures may prove critical since ARC puzzles are inherently visual.

2 The Abstract Reasoning Corpus (ARC) challenge and related work

This section presents the ARC-AGI challenge and discusses leading approaches to solving it through a combination of program synthesis and transductive predictions.

2.1 The Abstract Reasoning Corpus (ARC) challenge

The ARC challenge, introduced by Chollet [11], is designed as a diagnostic tool to evaluate the gap between human and artificial intelligence. It consists of independent tasks that test core cognitive abilities considered fundamental to human intelligence. These tasks draw on the work of developmental psychologists Spelke and Kinzler [44], who propose that human cognition is grounded in four basic systems that allow: (a) discerning objects and their mechanics, (b) understanding goal-directed agents, (c) grasping numbers and ordering principles, and (d) navigating spatial and geometrical environments. These systems, also described as core knowledge [44], enable us to perform fundamental tasks in the world. If an AI model succeeds on ARC tasks that require knowledge or skills derived from one or more of these systems, it would provide evidence that the model may share similar underlying cognitive structures with humans.

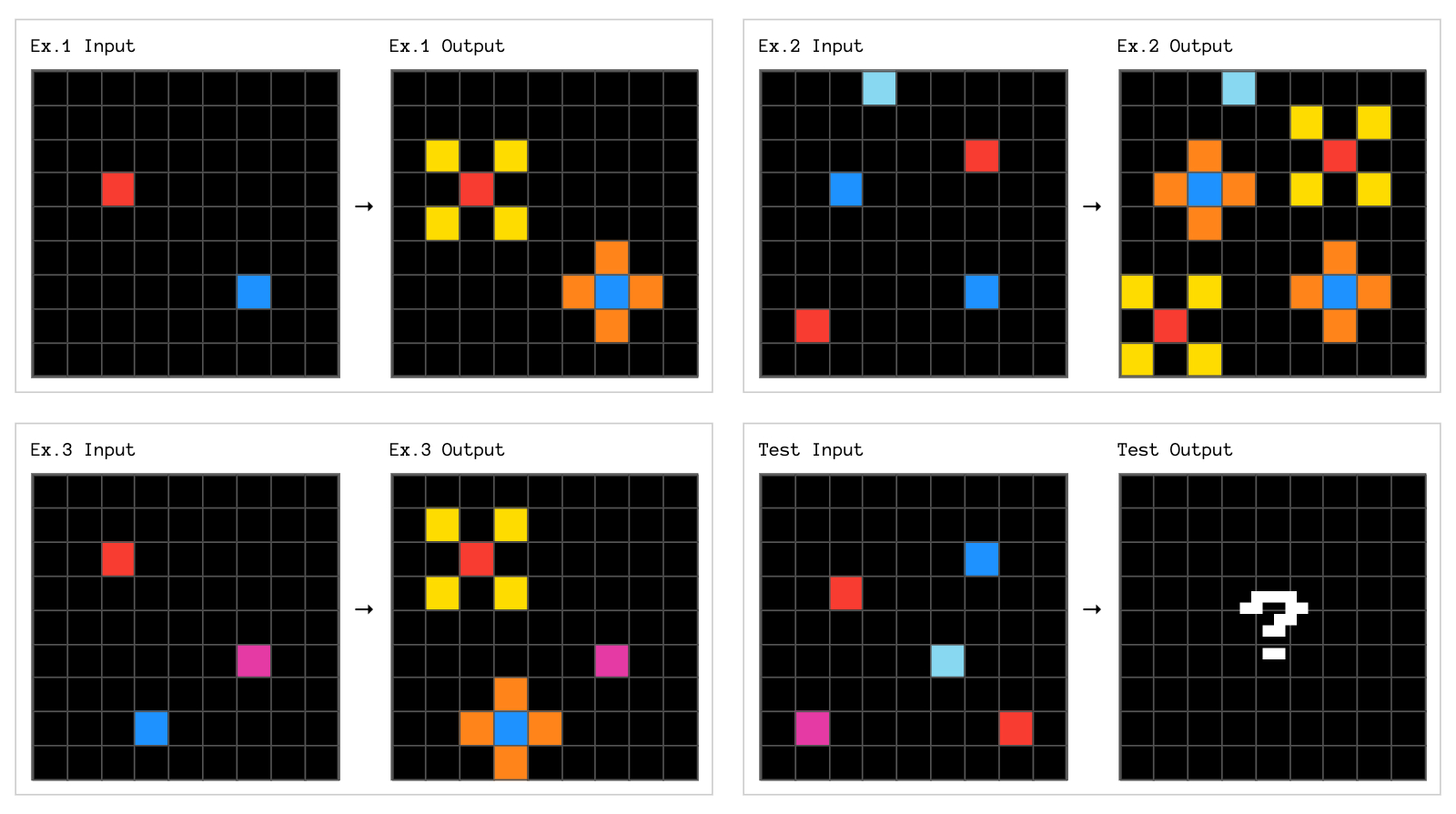

The ARC challenge (later renamed ARC-AGI-1 [12]) has translated these ideas about core knowledge into 2D visual puzzles (see Figure 1). The benchmark comprises 1,000 of them where each has a minimum of two demonstration pairs with a test input that is supposed to be solved based on the demonstration. In other words, the ARC-AGI-1 is a few-shot benchmark. Pairs are made up of two elements: an input grid and an output grid. The input grid is a rectangle that can vary in size, but never larger than 30 rows by 30 columns, with each cell taking on one of ten possible colors. The output grid is expected to be completely deducible on the basis of the properties of the input grid. Two guesses are allowed to pass each ARC test.

Figure 1: Example of an ARC 2D puzzle with demonstration pairs and another test input to be solved. The figure is from [12].

Most importantly, the benchmark is designed to resist memorization and instead reward strong generalization skills. Each task is unique and follows its own logic, yet still allows participants to infer the underlying procedure needed to solve it. To limit brute-force learning, ARC-AGI-1 is kept deliberately small. It consists of 1,000 tasks divided into four splits: (1) a public training set of 400 examples, (2) a public evaluation set of 400 similar but more challenging tasks, (3) a semi-private evaluation set of 100 tasks, and (4) a fully private evaluation set of 100 tasks to prevent leakage. The challenge also imposes computational constraints: competitive submissions must run in a single Kaggle notebook, with a maximum of 12 hours on one P100 GPU.

According to Chollet [11], ARC-AGI-1 puzzles are generally easy for humans. Nevertheless, LeGris et al. [27] report that, on average, humans solve only 61.6% of the tasks in the public evaluation set, with the best individuals reaching 97.8% accuracy. By comparison, the winning approach [18] of the ARC Prize from 2024 achieved 71.6% accuracy on the public evaluation set and 53.5% on ARC tests from the private evaluation set. This raises the question whether we have already achieved AI that masters core knowledge as well as humans. I will discuss it with respect to the new and upcoming benchmarks ARC-AGI-2 and ARC-AGI-3 in section 4.

The latest iteration of the ARC-AGI-1 challenge, in the form of the ARC Prize, from 2024, has been accompanied by several promising developments [12]: (a) large language model (LLM) based program synthesis to generate programs solving the ARC tasks [19, 28], (b) test-time training (TTT) for transductive models [3, 18], readjusting the model’s weights on the spot before making predictions, and (c) combining program synthesis with transductive models [28].

2.2 Combining induction and transduction for abstract reasoning

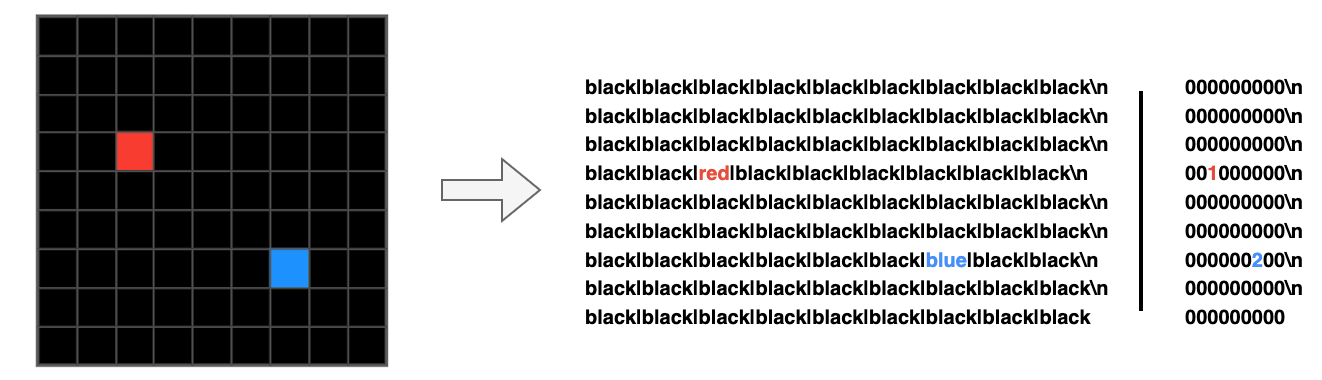

The winning paper from Li et al. [28] of the ARC Prize 2024 combines program synthesis (which the authors call ’induction’) with a transductive model using TTT in one ensemble. For induction as well as transduction, Li et al. [28] convert the ARC tasks into strings using one token per grid cell with newlines to indicate the end of rows (consider Figure 2). Both approaches were realized by fine-tuning a Llama 8B-Instruct model [14] on an enlarged dataset of ARC-like tasks (400k examples). Li et al. [28] generated this dataset with GPT4o-mini [24] based on natural language descriptions and manually written seed programs for 100 ARC-AGI-1 tasks. Li et al. [28] further collected training examples from sources such as Hodel [22].

The synthesis of the programs is achieved by letting Llama-8B-Instruct generate Python programs that can map an ARC input to the desired output solution. In contrast to previous synthetic approaches for ARC [9, 2], Li et al. [28] do not create a domain-specific language (DSL) for this purpose, but stick to Python. During the fine-tuning of the LLM, generated programs are compared with correct ones from their synthetic ARC dataset, where they added programs to each example.

The transductive Llama-8B-Instruct model is also fine-tuned to directly generate solution sequences for ARC tasks. To improve prediction, Li et al. [28] apply TTT. Following the approach of Sun et al. [45], this strategy introduces an additional self-supervised training step before each prediction. Specifically, the input is augmented (e.g., through rotations or color permutations), and the model is tasked with recovering the original version. If it fails, its weights are updated accordingly. Interestingly, this process not only improves the model’s ability to handle such reversions, but also encourages it to learn auxiliary features that transfer to the downstream task – in this case, producing the correct output for a given ARC test input.

By combining program synthesis with transduction via TTT and applying reranking to predict the most likely output across multiple augmentations, Li et al. [28] report a 56.75% accuracy for their ensemble approach on the public ARC-AGI-1 evaluation set. One of their key findings is that induction and transduction “are strongly complementary, even when trained on the same problems” [28]. The authors stipulate that inductive program synthesis might resemble a deliberate approach and transduction an intuitive, where both leverage different forms of reasoning, comparable to system-2 and system-1 reasoning as introduced by Kahneman [25]. Their finding suggests that even within the ARC’s core knowledge tasks the problems are of such different nature that they also require different forms of reasoning.

Although the results reported by Li et al. [28] are impressive, their approach relies heavily on large amounts of synthetic data designed to mimic ARC-AGI-1, raising concerns about potential overfitting. In addition, the use of an ensemble introduces operational complexity by requiring the coordination of two separate models. A unified architecture would ideally mitigate these issues by reducing fragmentation and simplifying deployment.

3 Motivating multimodal reasoning to solve ARC-AGI

The complementary nature of inductive and transductive reasoning underscores the diversity of reasoning strategies that can be deployed for tasks like ARC. Some ARC tasks can be effectively solved with deterministic, symbolic algorithms (i.e., Python programs), whereas others are more amenable to transductive predictions (i.e., patterns arising from neural activations). This points to the value of integrating two distinct reasoning paradigms: symbolic and neural approaches to AI. Yet, I propose broadening this perspective even further: reasoning may manifest in additional forms across different modalities, such as vision or other sensory perception. This consideration is particularly relevant because the ARC-AGI-1 puzzles are presented in a two-dimensional (2D) visual format.

Therefore, this section emphasizes that reasoning does not necessarily depend on language. It also examines the difference between 2D and 1D representations of ARC puzzles and how these may affect the performance of LLMs. Finally, it introduces multimodal large language models (MLLMs) as potential models for tackling ARC challenges.

3.1 Evidence for non-linguistic reasoning

Do we think in language? Fedorenko and Varley [15] review evidence from cognitive neuroscience addressing this long-standing question, drawing on findings from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies and from research on individuals with global aphasia. They argue that reasoning in domains such as arithmetic, music processing, spatial navigation, executive functions, and theory of mind does not depend on language. Specifically, fMRI evidence shows that brain regions involved in linguistic processing are not necessarily active when humans engage in arithmetic, logical, or functional reasoning, process music, or recognize others’ internal states. Furthermore, people with severe damage to language-related brain regions can still perform tasks in these domains. In sum, Fedorenko and Varley [15] conclude that various forms of thought and reasoning are possible without relying on language or the cognitive brain areas underlying language processing.

Ainooson et al. [2] compare the ARC-AGI-1 challenge with Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM) which is an intelligence test that touches on similar abilities and tasks as ARC. Studies with neurodivergent individuals who excel in visual imagery showed that these individuals scored differently – and often more strongly – on the test [43]. This led to the assumption that the tests can be solved with mental representations that are not necessarily linguistic, but retinotopic, that is, visually grounded [37]. Further imagery-based methods were developed that successfully helped solving the RPM tests with visual reasoning alone [31]. These experiments provide evidence that reasoning as well as reasoning about core knowledge tasks can be language independent.

In other words, the evidence from cognitive science and psychology suggest that thinking and reasoning can be performed in different modal domains. As humans can reason visually without language, ARC solvers may need non-linguistic pathways as well. This does not mean that reasoning is entirely non-linguistic, since much of our thinking is indeed processed through language – as is evident from inner monologues and the many textual representations of reasoning problems. Even so, it is important not to conflate the content of reasoning with the underlying cognitive processes.

Theories of mind debate whether mental states have linguistic properties. This idea is most prominently proposed by the language of thought hypothesis from Fodor [16] and Fodor and Pylyshyn [17]. According to this hypothesis, mental states are “symbolic structures, which typically have semantically evaluable constituents, and […] mental processes are rule-governed manipulations of them that are sensitive to their constituent structure” [38]. In other words, if we truly ’think in language’ our thought processes would be governed by a syntax-like structure, and the elements of our thought would be semantic-like objects. Opposing views, for example, from the Connectionist strain [30, 41, 42], argue that mental states originate from activation patterns – also referred to as ’nodes’ – within a neural network. Mental processes spread these patterns. However, the ’nodes’ have no semantic characteristics; for example, they do not refer to entities in this world. Activations are neither governed by strict grammar-like rules.

In summary, reasoning can take different forms, such as transductive or algorithmic, and can deal with various modalities, like language or visual input. Given this, it is reasonable to assume that any AI system capable of mastering core human knowledge across diverse contexts – especially within the ARC-AGI-1 framework with which we are concerned – would also be able to reason using these different forms and modalities.

3.2 Architectural bias: from 2D to 1D

Xu et al. [47] conduct a failure analysis of GPT-4’s performance on ARC puzzles. Specifically, they argue that the model’s reliance on textual encodings and its inherently sequential processing of ARC’s 2D input-output grids impede effective problem solving. Their argument is supported by three empirical observations. First, when ARC objects are linearized into sequences of strings (as is done by the majority of approaches to ARC, like [18, 28] – consider Figure 2), GPT-4 exhibits higher accuracy on tasks involving horizontal object movements than on otherwise analogous tasks requiring vertical movements, indicating a bias introduced by the LLM’s sequential processing. Second, translating ARC tasks into a DSL (with standardized object descriptions and coordinates) that explicitly foregrounds object-level structures approximately doubles GPT-4’s accuracy. Third, Xu et al. [47] introduce 1D-ARC, a simplified variant of ARC in which puzzles are reduced to one-dimensional tasks designed to capture the same core knowledge priors. In combination with the DSL, GPT-4 achieves near-perfect performance on 1D-ARC.

Figure 2: Example of an ARC 2D grid that is translated into 1D sequential representations where each grid cell is either represented with a text string (left) or a number (right). New lines are indicated with “\n”.

The experiments by Xu et al. [47] show that the current Transformer architecture configuration [46], which underpins GPT-4 and most other LLMs applied to ARC [18, 28], is biased toward sequential tasks. They further demonstrate that performance improves significantly when the puzzles’ visual representations are converted into quasi-linguistic forms. This suggests that models not constrained to 1D sequential data, and capable of processing visual inputs, would be well suited for solving puzzles from ARC-AGI-1.

3.3 Multimodal reasoning models

Puget [39] develop a 2D Transformer model to solve ARC-AGI-1 puzzles. The model’s architecture is similar to GPT-2 [40], but it takes 2D grids as input rather than 1D sequences. This is achieved through a 2D attention mechanism, which attends to all cells in the same row of a given grid cell as well as to all cells in the same column. Puget [39] report that using an attention mechanism attending to all cells reduced performance in experiments. By permuting colors and applying rotations and transpositions to ARC-AGI-1 puzzles, they generate 335 million samples to train the model. Combined with TTT, their 42M-parameter model achieves 17% on the public evaluation set.

While Puget [39] focused on a single modality, that is, visual input, their results illustrate the promise of addressing the 1D sequential bias. Yet human-level reasoning involves more than visual 2D pattern recognition; it requires integration with abilities such as counting or reasoning about goal-directed objects. This motivates multimodal architectures, which can combine visual processing with other cognitive capacities.

Most MLLMs, including Flamingo [4], PaLM-E [13], LLaVA [29], GPT-4o [24], and Claude3-Opus/Sonnet [5], accept both visual and textual inputs and generate textual outputs. Rather than adopting specialized 2D attention, they linearize visual inputs into sequences of tokens, enabling integration with language modeling. Nevertheless the aligned training from visual and textual inputs turns them into powerful models for cross-modal tasks. However, early attempts to apply them to ARC were unsuccessful: Xu et al. [47] found that GPT-4V [35] produced no meaningful results. Reasons for this failure could be shallow tokenization of the pixel-level structure needed for ARC tasks, a mismatch between the training distribution of GPT-4V and ARC-AGI-1, or the model’s over-reliance on language. More recently, private submissions of MLLMs (e.g., OpenAI’s o3 [36]) have reported strong performance, achieving 53% on the semi-private evaluation set [26].

It is interesting to note that research on multimodal models for ARC remains limited. I hypothesize that this partly due to computational constraints in the ARC Prize challenge, which restricts participants to a single 12-hour Kaggle runtime on one P100 GPU. Scaling studies [1] suggest that synergies across modalities in Transformer-based architectures emerge only at sizes of ~30B parameters or more. This implies that current competition settings may under-resource multimodal approaches, even though they may ultimately prove the most suitable paradigm for ARC.

4 Future research directions in multimodal reasoning

Ultimately, we want models that reason with different modal inputs and based on different strategies, transductively and algorithmically. This section discusses possible research approaches to bring us closer to this vision and to solving ARC puzzles.

4.1 Solving ARC-AGI-1 with multimodal models

To explore whether multimodal capabilities can improve a model’s predictive performance on ARC puzzles, one could adopt a strategy similar to the combination of induction and transduction proposed by Li et al. [28]. Rather than ensembling an inductive and a transductive model, this approach would ensemble a purely linguistic LLM with a MLLM that processes both text and vision inputs. If the hypothesis of this article is correct – that visual reasoning differs from linguistic reasoning and can support more accurate predictions of ARC grids – then comparing an LLM with a VLM should also yield complementary results. While prior work with GPT-4V [47] has not shown success, a comparison involving more recent models such as the LLMs Qwen2.5 [48] or Mistral Large 2 [32] and their multimodal counterparts, Qwen2.5-VL [7] or Pixtral Large [33], would be valuable. Eventually, the question would be if a multimodal VLM alone could suffice to solve ARC puzzles.

This line of research could be strengthened by incorporating interpretability methods to better understand how models realize reasoning on ARC. Drawing inspiration from cognitive studies such as Fedorenko and Varley [15], which examine reasoning in humans, one could apply neurolinguistic-style probing techniques to LLMs [20, 21]. For instance, a subset of hidden states from a model – alongside randomly generated states – could be used to train a simple classifier on a downstream task derived from an ARC puzzle. If the hidden states encode task-relevant information, the classifier should outperform those trained on random states. An especially compelling question is whether VLMs mobilize different hidden states than their purely linguistic counterparts (LLMs) in such experiments.

A different approach that could strengthen visual reasoning for ARC could be realized with Sketchpad [23]. Sketchpad is a framework that helps MLLMs, such as GPT-4o, with additional tool calls to dissect, enhance, or mark images and plot additional figures. For example, a sliding window for a visual input can be used to help the model focus on parts of an image. While this approach increases the GPT-4o abilities on vision tasks by 8.6% [23], it is conceivable that similar tools could help an MLLM with ARC. Again, it would be interesting if such vision focused model with visual tools would perform differently than its linguistic counterpart.

Finally, a long-term project should focus on developing an architecture in the spirit of Puget [39] that effectively integrates both 2D and 1D inputs and pay appropriate attention to visual aspects. Although many current MLLMs have an alignment between visual and linguistic tokens, visual aspects are still not properly considered in many models’ context according to recent studies [8]. Therefore, existing VLMs may be further improved by techniques such as Dynamic Attention ReAllocation [10], which help models give proper weight to visual cues that are often overlooked in favor of textual patterns.

4.2 ARC-AGI-2 and ARC-AGI-3

With respect to the strong performance of the approaches [18, 28, 36] in the 2024 ARC-AGI-1 challenge, Chollet et al. [12] highlight several shortcomings. They argue that the public evaluation set of 100 tasks has effectively become a training signal for participants, diminishing its novelty and encouraging overfitting. Moreover, they report that 49% of the evaluation tasks could be solved by brute-force program search, which they regard as inadequate for measuring the kind of generalization humans demonstrate when solving ARC puzzles from demonstration pairs.

To address these issues while maintaining the overall structure of ARC-AGI-1, Chollet et al. [12] plan to launch ARC-AGI-2 with new puzzles for the 2025 ARC Prize. They also outline ARC-AGI-3, scheduled for 2026, which will feature similarly structured tasks but with interactive elements, such as moving bars [6]. Transforming ARC into an interactive benchmark foreshadows a paradigm shift that could further strengthen MLLMs, as these models are naturally well suited to handle interactive inputs. In particular, models trained within more dynamic, realistic environments – such as EmbodiedGPT [34] – represent promising candidates for interactive reasoning to tackle ARC-AGI-3.

Beyond technical concerns, a deeper question arises about ARC’s validity as a benchmark for human-like reasoning. The framework is inspired by core knowledge theories, yet its 2D grid puzzles may measure abstract symbol manipulation rather than genuinely grounded reasoning about objects, agents, or space. Moreover, ARC’s anthropocentric orientation risks equating human-like performance with intelligence, overlooking the possibility that alternative, non-human strategies could be equally valid forms of reasoning. As such, while ARC-AGI-2 and -3 introduce new tasks to mitigate overfitting, they may still inherit structural limitations from ARC’s original design.

Conclusion

Solving the ARC-AGI challenge requires moving beyond single paradigms. Symbolic program synthesis and transductive prediction demonstrate clear complementarities, but their current reliance on sequential, language-based encodings limits their ability to fully capture the visual and structural nature of ARC puzzles. This article has argued that multimodal reasoning offers a path forward: by integrating visual, algorithmic, and transductive strategies within unified models, we can move closer to the kind of flexible, general intelligence that ARC is designed to probe.

Looking ahead, multimodal approaches should be systematically evaluated against purely linguistic models, not only in terms of accuracy but also in terms of error profiles, interpretability, and robustness across different puzzle types. Future ARC iterations such as ARC-AGI-2 and ARC-AGI-3 will provide fertile ground for such experiments, especially as they introduce new puzzles and interactive elements that align naturally with embodied and multimodal reasoning.

Bibliography

[1] Aghajanyan, A., Yu, L., Conneau, A., Hsu, W.-N., Hambardzumyan, K., Zhang, S., Roller, S., Goyal, N., Levy, O., and Zettlemoyer, L. (2023). Scaling laws for generative mixed-modal language models. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

[2] Ainooson, J., Sanyal, D., Michelson, J., Yang, Y., and Kunda, M. (2023). A neurodiversity-inspired solver for the abstraction reasoning corpus (arc) using visual imagery and program synthesis.

[3] Akyürek, E., Damani, M., Zweiger, A., Qiu, L., Guo, H., Pari, J., Kim, Y., and Andreas, J. (2024). The surprising effectiveness of test-time training for few-shot learning. arXiv preprint, 2505.07859.

[4] Alayrac, J.-B., Donahue, J., Luc, P., Miech, A., Barr, I., Hasson, Y., Lenc, K., Mensch, A., Millican, K., Reynolds, M., Ring, R., Rutherford, E., Cabi, S., Han, T., Gong, Z., Samangooei, S., Monteiro, M., Menick, J., Borgeaud, S., Brock, A., Nematzadeh, A., Sharifzadeh, S., Binkowski, M., Barreira, R., Vinyals, O., Zisserman, A., and Simonyan, K. (2022). Flamingo: a visual language model for few-shot learning. arXiv preprint, abs/2204.14198.

[5] Anthropic (2024). The claude 3 model family: Opus, sonnet, haiku.

[6] ARC Prize Foundation (2025). Arc-agi-3: Interactive reasoning benchmark. https://arcprize.org/arc-agi/3/. ARC-AGI-3 is currently in development: early preview limited to six games (three public and three scheduled for release in August 2025); development began in early 2025 and full launch expected in 2026.

[7] Bai, S., Chen, K., Liu, X., Wang, J., Ge, W., Song, S., Dang, K., Wang, P., Wang, S., Tang, J., Zhong, H., Zhu, Y., Yang, M., Li, Z., Wan, J., Wang, P., Ding, W., Fu, Z., Xu, Y., Ye, J., Zhang, X., Xie, T., Cheng, Z., Zhang, H., Yang, Z., Xu, H., and Lin, J. (2025). Qwen2.5-vl technical report. arXiv preprint, 2502.13923.

[8] Baldassini, F. B., Shukor, M., Cord, M., Soulier, L., and Piwowarski, B. (2024). What makes multimodal in-context learning work? 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), pages 1539–1550.

[9] Butt, N., Manczak, B., Wiggers, A. J., Rainone, C., Zhang, D. W., Defferrard, M., and Cohen, T. (2024). Codeit: Self-improving language models with prioritized hindsight replay. arXiv preprint, 2402.04858.

[10] Chen, S., Liu, J., Han, Z., Xia, Y., Cremers, D., Torr, P. H. S., Tresp, V., and Gu, J. (2025). True multimodal in-context learning needs attention to the visual context. arXiv preprint, 2507.15807.

[11] Chollet, F. (2019). On the measure of intelligence. arXiv preprint, 1911.01547.

[12] Chollet, F., Knoop, M., Kamradt, G., and Landers, B. (2024). Arc prize 2024: Technical report. arXiv preprint, 2412.04604.

[13] Driess, D., Xia, F., Sajjadi, M. S. M., Lynch, C., Chowdhery, A., Ichter, B., Wahid, A., Tompson, J., Vuong, Q. H., Yu, T., Huang, W., Chebotar, Y., Sermanet, P., Duckworth, D., Levine, S., Vanhoucke, V., Hausman, K., Toussaint, M., Greff, K., Zeng, A., Mordatch, I., and Florence, P. R. (2023). Palm-e: An embodied multimodal language model. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

[14] Dubey, A., Jauhri, A., Pandey, A., Kadian, A., Al-Dahle, A., Letman, A., Mathur, A., Schelten, A., Yang, A., Fan, A., Goyal, A., Hartshorn, A. S., Yang, A., Mitra, A., Sravankumar, A., Korenev, A., Hinsvark, A., Rao, A., Zhang, A., Rodriguez, A., Gregerson, A., Spataru, A., Rozière, B., Biron, B., Tang, B., Chern, B., Caucheteux, C., Nayak, C., Bi, C., Marra, C., McConnell, C., Keller, C., Touret, C., Wu, C., Wong, C., tian Cantón Ferrer, C., Nikolaidis, C., Allonsius, D., Song, D., Pintz, D., Livshits, D., Esiobu, D., Choudhary, D., Mahajan, D., Garcia-Olano, D., Perino, D., Hupkes, D., Lakomkin, E., AlBadawy, E. A., Lobanova, E., Dinan, E., Smith, E. M., Radenovic, F., Zhang, F., Synnaeve, G., Lee, G., Anderson, G. L., Nail, G., Mialon, G., Pang, G., Cucurell, G., Nguyen, H., Korevaar, H., Xu, H., Touvron, H., Zarov, I., Ibarra, I. A., Kloumann, I. M., Misra, I., Evtimov, I., Copet, J., Lee, J., Geffert, J., Vranes, J., Park, J., Mahadeokar, J., Shah, J., van der Linde, J., Billock, J., Hong, J., Lee, J., Fu, J., Chi, J., Huang, J., Liu, J., Wang, J., Yu, J., Bitton, J., Spisak, J., Park, J., Rocca, J., Johnstun, J., Saxe, J., Jia, J.-Q., Alwala, K. V., Upasani, K., Plawiak, K., Li, K., neth Heafield, K.-., Stone, K. R., El-Arini, K., Iyer, K., Malik, K., ley Chiu, K., Bhalla, K., Rantala-Yeary, L., van der Maaten, L., Chen, L., Tan, L., Jenkins, L., Martin, L., Madaan, L., Malo, L., Blecher, L., Landzaat, L., de Oliveira, L., Muzzi, M., Pasupuleti, M., Singh, M., Paluri, M., Kardas, M., Oldham, M., Rita, M., Pavlova, M., Kambadur, M. H. M., Lewis, M., Si, M., Singh, M. K., Hassan, M., Goyal, N., Torabi, N., lay Bashlykov, N., Bogoychev, N., Chatterji, N. S., Duchenne, O., cCelebi, O., Alrassy, P., Zhang, P., Li, P., Vasi´ c, P., Weng, P., Bhargava, P., Dubal, P., Krishnan, P., Koura, P. S., Xu, P., He, Q., Dong, Q., Srinivasan, R., Ganapathy, R., Calderer, R., Cabral, R. S., Stojnic, R., Raileanu, R., Girdhar, R., Patel, R., Sauvestre, R., nie Polidoro, R., Sumbaly, R., Taylor, R., Silva, R., Hou, R., Wang, R., Hosseini, S., hana Chennabasappa, S., Singh, S., Bell, S., Kim, S. S., Edunov, S., Nie, S., Narang, S., Raparthy, S. C., Shen, S., Wan, S., Bhosale, S., Zhang, S., Vandenhende, S., Batra, S., Whitman, S., Sootla, S., Collot, S., Gururangan, S., Borodinsky, S., Herman, T., Fowler, T., Sheasha, T., Georgiou, T., Scialom, T., Speckbacher, T., Mihaylov, T., Xiao, T., Karn, U., Goswami, V., Gupta, V., Ramanathan, V., Kerkez, V., Gonguet, V., ginie Do, V., Vogeti, V., Petrovic, V., Chu, W., Xiong, W., Fu, W., ney Meers, W., Martinet, X., Wang, X., Tan, X. E., Xie, X., Jia, X., Wang, X., Goldschlag, Y., Gaur, Y., Babaei, Y., Wen, Y., Song, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Mao, Y., Coudert, Z. D., Yan, Z., Chen, Z., Papakipos, Z., Singh, A. K., Grattafiori, A., Jain, A., Kelsey, A., Shajnfeld, A., Gangidi, A., Victoria, A., Goldstand, A., Menon, A., Sharma, A., Boesenberg, A., Vaughan, A., Baevski, A., Feinstein, A., Kallet, A., Sangani, A., Yunus, A., Lupu, A., Alvarado, A., Caples, A., Gu, A., Ho, A., Poulton, A., Ryan, A., Ramchandani, A., Franco, A., Saraf, A., Chowdhury, A., Gabriel, A., Bharambe, A., Eisenman, A., Yazdan, A., James, B., Maurer, B., Leonhardi, B., Huang, P.-Y. B., Loyd, B., de Paola, B., Paranjape, B., Liu, B., Wu, B., Ni, B., Hancock, B., Wasti, B., Spence, B., Stojkovic, B., Gamido, B., Montalvo, B., Parker, C., Burton, C., Mejia, C., Wang, C., Kim, C., Zhou, C., Hu, C., Chu, C.-H., Cai, C., Tindal, C., Feichtenhofer, C., Civin, D., Beaty, D., Kreymer, D., Li, S.-W., Wyatt, D., Adkins, D., Xu, D., Testuggine, D., David, D., Parikh, D., Liskovich, D., Foss, D., Wang, D., Le, D., Holland, D., Dowling, E., Jamil, E., Montgomery, E., Presani, E., Hahn, E., Wood, E., Brinkman, E., Arcaute, E., Dunbar, E., Smothers, E., Sun, F., Kreuk, F., Tian, F., Ozgenel, F., Caggioni, F., Guzm’an, F., Kanayet, F. J., Seide, F., Florez, G. M., Schwarz, G., Badeer, G., Swee, G., Halpern, G., Thattai, G., Herman, G., Sizov, G. G., Zhang, G., Lakshminarayanan, G., Shojanazeri, H., Zou, H., Wang, H., Zha, H., Habeeb, H., Rudolph, H., Suk, H., Aspegren, H., Goldman, H., Molybog, I., Tufanov, I., Veliche, I.-E., Gat, I., Weissman, J., Geboski, J., Kohli, J., Asher, J., Gaya, J.-B., Marcus, J., Tang, J., Chan, J., Zhen, J., Reizenstein, J., Teboul, J., Zhong, J., Jin, J., Yang, J., Cummings, J., Carvill, J., Shepard, J., McPhie, J., Torres, J., Ginsburg, J., Wang, J., Wu, K., KamHou, U., Saxena, K., Prasad, K., Khandelwal, K., Zand, K., Matosich, K., Veeraraghavan, K., Michelena, K., Li, K., Huang, K., Chawla, K., Lakhotia, K., Huang, K., Chen, L., Garg, L., Lavender, A., Silva, L., Bell, L., Zhang, L., Guo, L., Yu, L., Moshkovich, L., Wehrstedt, L., Khabsa, M., Avalani, M., Bhatt, M., Tsimpoukelli, M., Mankus, M., Hasson, M., Lennie, M., Reso, M., Groshev, M., Naumov, M., Lathi, M., Keneally, M., Seltzer, M. L., Valko, M., Restrepo, M., Patel, M., Vyatskov, M., Samvelyan, M., Clark, M., Macey, M., Wang, M., Hermoso, M. J., Metanat, M., Rastegari, M., ish Bansal, M., Santhanam, N., Parks, N., White, N., ata Bawa, N., Singhal, N., Egebo, N., Usunier, N., Laptev, N. P., Dong, N., Zhang, N., Cheng, N., Chernoguz, O., Hart, O., Salpekar, O., Kalinli, O., Kent, P., Parekh, P., Saab, P., Balaji, P., dro Rittner, P., Bontrager, P., Roux, P., Dollár, P., Zvyagina, P., Ratanchandani, P., Yuvraj, P., Liang, Q., Alao, R., Rodriguez, R., Ayub, R., Murthy, R., Nayani, R., Mitra, R., Li, R., Hogan, R., Battey, R., Wang, R., Maheswari, R., Howes, R., Rinott, R., Bondu, S. J., Datta, S., Chugh, S., Hunt, S., Dhillon, S., Sidorov, S., Pan, S., Verma, S., Yamamoto, S., Ramaswamy, S., Lindsay, S., Feng, S., Lin, S., Zha, S. C., Shankar, S., Zhang, S., Wang, S., Agarwal, S., Sajuyigbe, S., Chintala, S., Max, S., Chen, S., Kehoe, S., Satterfield, S., Govindaprasad, S., Gupta, S. K., Cho, S.-B., Virk, S., Subramanian, S., Choudhury, S., Goldman, S., Remez, T., Glaser, T., Best, T., Kohler, T., Robinson, T., Li, T., Zhang, T., Matthews, T., Chou, T., Shaked, T., Vontimitta, V., Ajayi, V., Montanez, V., Mohan, V., Kumar, V. S., Mangla, V., Ionescu, V., Poenaru, V. A., Mihailescu, V. T., Ivanov, V., Li, W., Wang, W., Jiang, W., Bouaziz, W., Constable, W., Tang, X., Wang, X., Wu, X., Wang, X., Xia, X., Wu, X., Gao, X., Chen, Y., Hu, Y., Jia, Y., Qi, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Adi, Y., Nam, Y., Wang, Y., Hao, Y., Qian, Y., He, Y., Rait, Z., DeVito, Z., Rosnbrick, Z., Wen, Z., Yang, Z., and Zhao, Z. (2024). The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint, 2407.21783.

[15] Fedorenko, E. and Varley, R. A. (2016). Language and thought are not the same thing: evidence from neuroimaging and neurological patients. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1369.

[16] Fodor, J. (1975). The Language of Thought. Harvard University Press.

[17] Fodor, J. A. and Pylyshyn, Z. W. (1988). Connectionism and cognitive architecture: A critical analysis. Cognition, 28(1):3–71.

[18] Franzen, D., Disselhoff, J., and Hartmann, D. (2025). Product of experts with llms: Boosting performance on arc is a matter of perspective. arXiv preprint.

[19] Greenblatt, R. (2024). Submission for arc prize. https://www.kaggle.com/code/rgreenblatt/rg- basic-ported-submission?scriptVersionId=184981551.

[20] He, L., Chen, P., Nie, E., Li, Y., and Brennan, J. R. (2024). Decoding probing: Revealing internal linguistic structures in neural language models using minimal pairs. In Calzolari, N., Kan, M.-Y., Hoste, V., Lenci, A., Sakti, S., and Xue, N., editors, Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), pages 4488–4497, Torino, Italia. ELRA and ICCL.

[21] He, L., Nie, E., Schmid, H., Schuetze, H., Mesgarani, N., and Brennan, J. (2025). Large language models as neurolinguistic subjects: Discrepancy between performance and competence. In Che, W., Nabende, J., Shutova, E., and Pilehvar, M. T., editors, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics

[22] Hodel, M. (2024). Rearc. https://github.com/michaelhodel/re-arc.

[23] Hu, Y., Shi, W., Fu, X., Roth, D., Ostendorf, M., Zettlemoyer, L., Smith, N. A., and Krishna, R. (2024). Visual sketchpad: Sketching as a visual chain of thought for multimodal language models. In Globerson, A., Mackey, L., Belgrave, D., Fan, A., Paquet, U., Tomczak, J., and Zhang, C., editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 37, pages 139348–139379. Curran Associates, Inc.

[24] Hurst, A., Lerer, A., Goucher, A. P., Perelman, A., Ramesh, A., Clark, A., Ostrow, A., Welihinda, A., Hayes, A., Radford, A., Mkadry, A., Baker-Whitcomb, A., Beutel, A., Borzunov, A., Carney, A., Chow, A., Kirillov, A., Nichol, A., Paino, A., Renzin, A., Passos, A., Kirillov, A., Christakis, A., Conneau, A., Kamali, A., Jabri, A., Moyer, A., Tam, A., Crookes, A., Tootoochian, A., Tootoonchian, A., Kumar, A., Vallone, A., Karpathy, A., Braunstein, A., Cann, A., Codispoti, A., Galu, A., Kondrich, A., Tulloch, A., drey Mishchenko, A., Baek, A., Jiang, A., toine Pelisse, A., Woodford, A., Gosalia, A., Dhar, A., Pantuliano, A., Nayak, A., Oliver, A., Zoph, B., Ghorbani, B., Leimberger, B., Rossen, B., Sokolowsky, B., Wang, B., Zweig, B., Hoover, B., Samic, B., McGrew, B., Spero, B., Giertler, B., Cheng, B., Lightcap, B., Walkin, B., Quinn, B., Guarraci, B., Hsu, B., Kellogg, B., Eastman, B., Lugaresi, C., Wainwright, C. L., Bassin, C., Hudson, C., Chu, C., Nelson, C., Li, C., Shern, C. J., Conger, C., Barette, C., Voss, C., Ding, C., Lu, C., Zhang, C., Beaumont, C., Hallacy, C., Koch, C., Gibson, C., Kim, C., Choi, C., McLeavey, C., Hesse, C., Fischer, C., Winter, C., Czarnecki, C., Jarvis, C., Wei, C., Koumouzelis, C., Sherburn, D., Kappler, D., Levin, D., Levy, D., Carr, D., Farhi, D., Mély, D., Robinson, D., Sasaki, D., Jin, D., Valladares, D., Tsipras, D., Li, D., Nguyen, P. D., Findlay, D., Oiwoh, E., Wong, E., Asdar, E., Proehl, E., Yang, E., Antonow, E., Kramer, E., Peterson, E., Sigler, E., Wallace, E., Brevdo, E., Mays, E., Khorasani, F., Such, F. P., Raso, F., Zhang, F., von Lohmann, F., Sulit, F., Goh, G., Oden, G., Salmon, G., Starace, G., Brockman, G., Salman, H., Bao, H.-B., Hu, H., Wong, H., Wang, H., Schmidt, H., Whitney, H., woo Jun, H., Kirchner, H., de Oliveira Pinto, H. P., Ren, ˙ H., Chang, H., Chung, H. W., Kivlichan, I., O’Connell, I., Osband, I., Silber, I., Sohl, I., Ibrahim Cihangir Okuyucu, Lan, I., Kostrikov, I., Sutskever, I., Kanitscheider, I., Gulrajani, I., Coxon, J., Menick, J., Pachocki, J. W., Aung, J., Betker, J., Crooks, J., Lennon, J., Kiros, J. R., Leike, J., Park, J., Kwon, J., Phang, J., Teplitz, J., Wei, J., Wolfe, J., Chen, J., Harris, J., Varavva, J., Lee, J. G., Shieh, J., Lin, J., Yu, J., Weng, J., Tang, J., Yu, J., Jang, J., Candela, J. Q., Beutler, J., Landers, J., Parish, J., Heidecke, J., Schulman, J., Lachman, J., McKay, J., Uesato, J., Ward, J., Kim, J. W., Huizinga, J., Sitkin, J., Kraaijeveld, J., Gross, J., Kaplan, J., Snyder, J., Achiam, J., Jiao, J., Lee, J., Zhuang, J., Harriman, J., Fricke, K., Hayashi, K., Singhal, K., Shi, K., Karthik, K., Wood, K., Rimbach, K., Hsu, K., Nguyen, K., Gu-Lemberg, K., Button, K., Liu, K., Howe, K., Muthukumar, K., Luther, K., Ahmad, L., Kai, L., Itow, L., Workman, L., Pathak, L., Chen, L., Jing, L., Guy, L., Fedus, L., Zhou, L., Mamitsuka, L., Weng, L., McCallum, L., Held, L., Long, O., Feuvrier, L., Zhang, L., Kondraciuk, L., Kaiser, L., Hewitt, L., Metz, L., Doshi, L., Aflak, M., Simens, M., laine Boyd, M., Thompson, M., Dukhan, M., Chen, M., Gray, M., Hudnall, M., Zhang, M., Aljubeh, M., teusz Litwin, M., Zeng, M., Johnson, M., Shetty, M., Gupta, M., Shah, M., Yatbaz, M. A., Yang, M., Zhong, M., Glaese, M., Chen, M., Janner, M., Lampe, M., Petrov, M., Wu, M., Wang, M., Fradin, M., Pokrass, M., Castro, M., Castro, M., Pavlov, M., Brundage, M., Wang, M., Khan, M., Murati, M., Bavarian, M., Lin, M., Yesildal, M., Soto, N., Gimelshein, N., talie Cone, N., Staudacher, N., Summers, N., LaFontaine, N., Chowdhury, N., Ryder, N., Stathas, N., Turley, N., Tezak, N. A., Felix, N., Kudige, N., Keskar, N. S., Deutsch, N., Bundick, N., Puckett, N., Nachum, O., Okelola, O., Boiko, O., Murk, O., Jaffe, O., Watkins, O., Godement, O., Campbell-Moore, O., Chao, P., McMillan, P., Belov, P., Su, P., Bak, P., Bakkum, P., Deng, P., Dolan, P., Hoeschele, P., Welinder, P., Tillet, P., Pronin, P., Tillet, P., Dhariwal, P., ing Yuan, Q., Dias, R., Lim, R., Arora, R., Troll, R., Lin, R., Lopes, R. G., Puri, R., Miyara, R., Leike, R. H., Gaubert, R., Zamani, R., Wang, R., Donnelly, R., Honsby, R., Smith, R., Sahai, R., Ramchandani, R., Huet, R., Carmichael, R., Zellers, R., Chen, R., Chen, R., Nigmatullin, R. R., Cheu, R., Jain, S., Altman, S., Schoenholz, S., Toizer, S., Miserendino, S., Agarwal, S., Culver, S., Ethersmith, S., Gray, S., Grove, S., Metzger, S., Hermani, S., Jain, S., Zhao, S., Wu, S., Jomoto, S., Wu, S., Xia, S., Phene, S., Papay, S., Narayanan, S., Coffey, S., Lee, S., Hall, S., Balaji, S., Broda, T., Stramer, T., Xu, T., Gogineni, T., Christianson, T., Sanders, T., Patwardhan, T., Cunninghman, T., Degry, T., Dimson, T., Raoux, T., Shadwell, T., Zheng, T., Underwood, T., Markov, T., Sherbakov, T., Rubin, T., Stasi, T., Kaftan, T., Heywood, T., Peterson, T., Walters, T., Eloundou, T., Qi, V., Moeller, V., Monaco, V., Kuo, V., Fomenko, V., Chang, W., Zheng, W., Zhou, W., Manassra, W., Sheu, W., Zaremba, W., Patil, Y., Qian, Y., Kim, Y., Cheng, Y., Zhang, Y., He, Y., Zhang, Y., Jin, Y., Dai, Y., and Malkov, Y. (2024). Gpt-4o system card. arXiv preprint, 2410.21276.

[25] Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking, fast and slow. Penguin, London.

[26] Kamradt, G. (2025). Analyzing o3 and o4-mini with arc-agi. https://arcprize.org/blog/analyzing-o3-with-arc-agi.

[27] LeGris, S., Vong, W. K., Lake, B. M., and Gureckis, T. M. (2025). A comprehensive behavioral dataset for the abstraction and reasoning corpus. Scientific Data, 12.

[28] Li, W.-D., Hu, K., Larsen, C., Wu, Y., Alford, S., Woo, C., Dunn, S. M., Tang, H., Naim, M., Nguyen, D., Zheng, W.-L., Tavares, Z., Pu, Y., and Ellis, K. (2024). Combining induction and transduction for abstract reasoning. arXiv preprint, 2411.02272.

[29] Liu, H., Li, C., Wu, Q., and Lee, Y. J. (2023). Visual instruction tuning. arXiv preprint, 2304.08485.

[30] McCulloch, W. S. and Pitts, W. (1943). A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, 5(4):115–133.

[31] McGreggor, K., Kunda, M., and Goel, A. K. (2014). Fractals and ravens. Artif. Intell., 215:1–23.

[32] Mistral AI (2024a). Large enough: Mistral large 2. https://mistral.ai/news/mistral-large-2407.

[33] Mistral AI (2024b). Pixtral large. https://mistral.ai/news/pixtral-large.

[34] Mu, Y., Zhang, Q., Hu, M., Wang, W., Ding, M., Jin, J., Wang, B., Dai, J., Qiao, Y., and Luo, P. (2023). Embodiedgpt: Vision-language pre-training via embodied chain of thought. arXiv preprint, 2305.15021.

[35] OpenAI (2023). Gpt-4v(ision) system card.

[36] OpenAI (2025). Openai o3 and o4-mini system card.

[37] Pearson, J. and Kosslyn, S. M. (2015). The heterogeneity of mental representation: Ending the imagery debate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112:10089 – 10092.

[38] Pitt, D. (2022). Mental Representation. In Zalta, E. N. and Nodelman, U., editors, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Fall 2022 edition.

[39] Puget, J.-F. (2024). A 2d ngpt model for arc prize. https://github.com/jfpuget/ARC-AGI- Challenge-2024/blob/main/arc.pdf. Presented as a solution to the ARC Prize 2024 competition on Kaggle.

[40] Radford, A., Wu, J., Child, R., Luan, D., Amodei, D., and Sutskever, I. (2019). Language models are unsupervised multitask learners.

[41] Rumelhart, D. E. (1997). The architecture of mind: A connectionist approach. In Mind Design II: Philosophy, Psychology, and Artificial Intelligence. The MIT Press.

[42] Rumelhart, D. E., McClelland, J. L., and Group, P. R. (1986). Parallel Distributed Processing, Volume 1: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition: Foundations. The MIT Press.

[43] Soulières, I., Dawson, M., Samson, F., Barbeau, E. B., Sahyoun, C. P., Strangman, G. E., Zeffiro, T. A., and Mottron, L. (2009). Enhanced visual processing contributes to matrix reasoning in autism. Human Brain Mapping, 30.

[44] Spelke, E. S. and Kinzler, K. D. (2007). Core knowledge. Developmental science, 10 1:89–96.

[45] Sun, Y., Wang, X., Liu, Z., Miller, J., Efros, A. A., and Hardt, M. (2019). Test-time training with self-supervision for generalization under distribution shifts. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

[46] Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N. M., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L., and Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Neural Information Processing Systems.

[47] Xu, Y. W., Li, W., Vaezipoor, P., Sanner, S., and Khalil, E. B. (2023). Llms and the abstraction and reasoning corpus: Successes, failures, and the importance of object-based representations. arXiv preprint, 2305.18354.

[48] Yang, A., Yang, B., Zhang, B., Hui, B., Zheng, B., Yu, B., Li, C., Liu, D., Huang, F., Dong, G., Wei, H., Lin, H., Yang, J., Tu, J., Zhang, J., Yang, J., Yang, J., Zhou, J., Lin, J., Dang, K., Lu, K., Bao, K., Yang, K., Yu, L., Li, M., Xue, M., Zhang, P., Zhu, Q., Men, R., Lin, R., Li, T., Xia, T., Ren, X., Ren, X., Fan, Y., Su, Y., Zhang, Y.-C., Wan, Y., Liu, Y., Cui, Z., Zhang, Z., Qiu, Z., Quan, S., and Wang, Z. (2024). Qwen2.5 technical report. arXiv preprint, 2412.15115.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: